Debuggers come in all shapes and sizes, offering a variety of options to track down your software problems and inspecting internal states at any given time. Yet some developers have a hard time breaking the habit of simply adding print statements into their code instead, performing manual work their tools could do for them. We say, to each their own — the best tools won’t be of much help if they are out of your comfort zone or work against your natural flow. Sometimes, a retrospective analysis using your custom-tailored debug output is just what you need to tackle an issue.

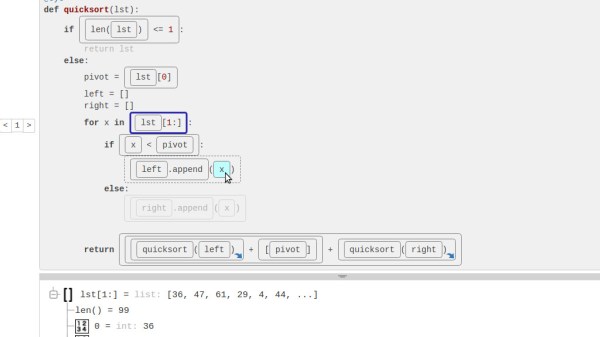

If the last part sounds familiar and your language of choice happens to be Python, [Alex Hall] created the Bird’s Eye Python debugger that records every expression inside a function and displays them interactively in a web browser. Every result, both partial and completed, and every value can then be inspected at any point inside each individual function call, turning this debugger into an educational tool along the way.

With a little bit of tweaking, the web interface can be made remote accessible, and for example, analyze code running on a Raspberry Pi. However, taking it further and using Bird’s Eye with MicroPython or CircuitPython would require more than just a little bit of tweaking, assuming there will be enough memory for it. Although it wouldn’t be first time that someone got creative and ran Python on a memory limited microcontroller.