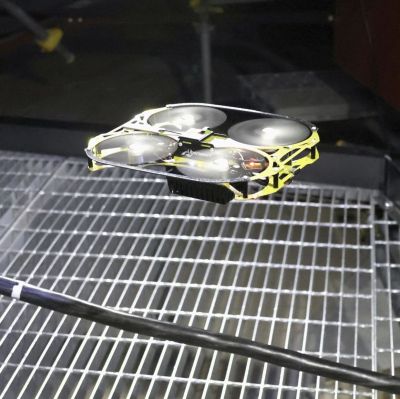

During a press event on January 23rd, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) demonstrated two new robots at the mock-up facility at Japan Atomic Energy Agency’s Naraha Center for Remote Control Technology Development (NARREC). As pictured by AP, one is a snake-like robot that should be able to reach very inaccessible areas, while four flying drones will be the first to enter the containment vessel of the Unit 1 reactor for inspection.

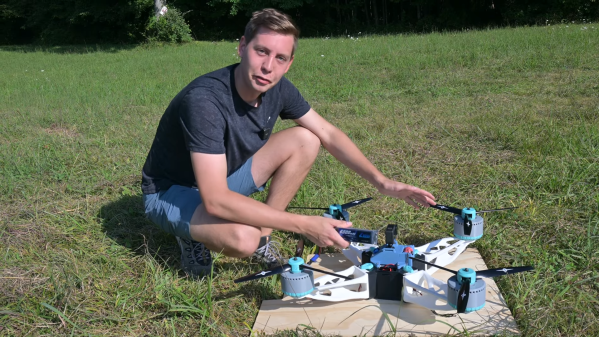

These flying drones are 20 cm across, weigh 185 grams each, and were adapted from an existing model that’s used for boiler inspections. At the Naraha Town facility, operators were able to practice flying it into a copy of the Unit 1’s containment vessel via the piping. As the most heavily damaged unit at the Fukushima Daiichi plant, engineers are interested to learn the details of the fuel and debris that has fallen to the bottom of the vessel so that the clean-up and decontamination steps can be planned.

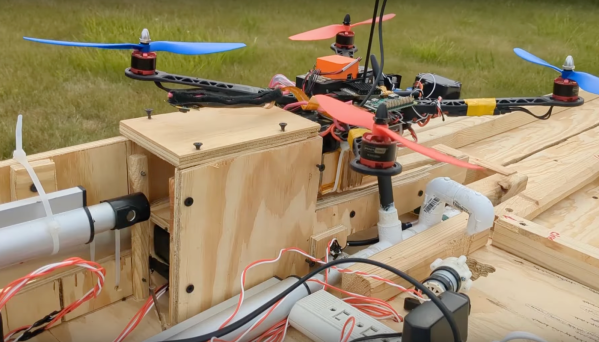

Most of the current work inside the Fukushimi Daiichi reactor buildings is performed by robots, with the TEPCO gallery providing an overview of the wide range of the types used so far.

One of the first was the PackBot, from US-based iRobot, with many more following for a variety of tasks, from inspection to debris clearing and even dry ice-based decontamination.