Old American radios (and we mean really old ones) took several kinds of batteries. The A battery powered the filaments (generally 1.5V at a high current draw). The B battery powered the plate (much lower current, but a higher voltage–typically 90V). In Britain these were the LT (low tension) and HT (high tension) batteries. If you want to rebuild and operate old radios, you have to come up with a way to generate that B voltage.

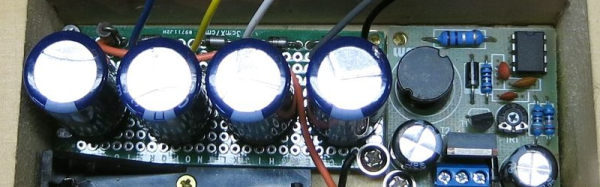

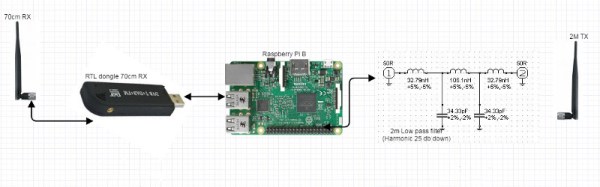

Most people opt to use an AC supply. You can daisy-chain a bunch of 9V batteries, but that really ruins the asthetics of the radio. [VA3NGC] had a better idea: he built a reproduction B battery from a wooden box, some brass hardware, a nixie tube power supply, and a 9V battery (which remains hidden). There’s also a handful of zener diodes, resistors, and capacitors to allow different taps depending on the voltage required.

The project looks great. The wooden box apparently was a recycle item and the brass hardware makes it look like it belongs with the old radios it powers. This is a good example of how there’s more to vintage restoration than just the electronics. Sure, the function is important, but to really enjoy the old gear, the presentation is important, too.

The project looks great. The wooden box apparently was a recycle item and the brass hardware makes it look like it belongs with the old radios it powers. This is a good example of how there’s more to vintage restoration than just the electronics. Sure, the function is important, but to really enjoy the old gear, the presentation is important, too.

Not all tube radios took 90V B+, but since this battery has taps, that isn’t a problem. The old Radio Shack P-Box kit took 22.5V. Of course, if you are going to build your own battery, maybe you ought to build your own triodes, too.