It seems [Kevin] has particularly bad luck with neighbors. His first apartment had upstairs neighbors who were apparently a dance troupe specializing in tap. His second apartment was a town house, which had a TV mounted on the opposite wall blaring American Idol with someone singing along very loudly. The people next to [Kevin]’s third apartment liked music, usually with a lot of bass, and frequently at seven in the morning. This happened every day until [Kevin] found a solution (Patreon, but only people who have adblock disabled may complain).

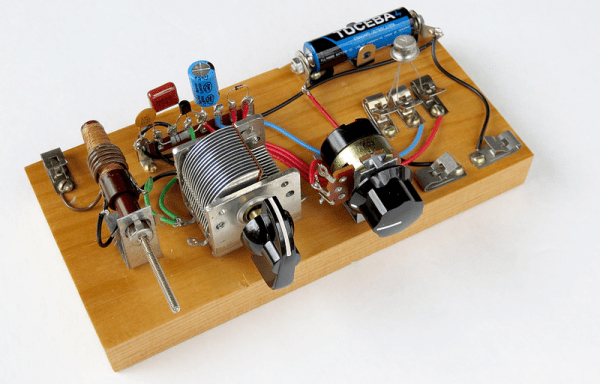

In a hangover-induced rage that began with thumping bass at 7AM on a Sunday, [Kevin] tore through his box of electronic scrap for every capacitor and inductor in his collection. An EMP was the only way to find any amount of peace in his life, and the electronics in his own apartment would be sacrificed for the greater good. In his fury, [Kevin] saw a Yaesu handheld radio sitting on his desk. Maybe, just maybe, if he pressed the transmit button on the right frequency, the speakers would click. The results turned out even better than expected.

With a car mount antenna pointed directly at the neighbor’s stereo, [Kevin] could transmit on a specific, obscure frequency and silence the speakers. How? At seven in the morning on a Sunday, you don’t ask questions. That’s a matter for when you tell everyone on the Internet.

Needless to say, using a radio to kill your neighbor’s electronics is illegal, and it might be a good idea for [Kevin] to take any references to this escapade off of the Internet. It would be an even better idea to not put his call sign online in the future.

That said, this is a wonderful tale of revenge. It’s not an uncommon occurrence, either. Wikihow, Yahoo Answers and Quora – the web pages ‘normies’ use for the questions troubling their soul – are sometimes unbelievably literate when it comes to unintentional electromagnetic interference, and some of the answers correctly point out grounding a stereo and putting a few ferrite beads on the speaker cables is the way to go. Getting this answer relies entirely on asking the right question, something I suspect 90% of the population is completely incapable of doing.

While [Kevin]’s tale is a grin-inducing two-minute read, You shouldn’t, under any circumstances, do anything like this. Polluting the airwaves is much worse than polluting your neighbor’s eardrums; one of them violates municipal noise codes and another is breaking federal law. It’s a good story, but don’t do it yourself.

Editor’s Note: Soon after publishing our article [Kevin] took down his post and sent us an email. He realized that what he had done wasn’t a good idea. People make mistakes and sometimes do things without thinking. But talking about why this was a bad idea is one way to help educate more people about responsible behavior. Knowing you shouldn’t do something even though you know how is one paving stone on the path to wisdom.

–Mike Szczys

By 1989, the film was out on VHS and laser disc. With high quality audio available,

By 1989, the film was out on VHS and laser disc. With high quality audio available,