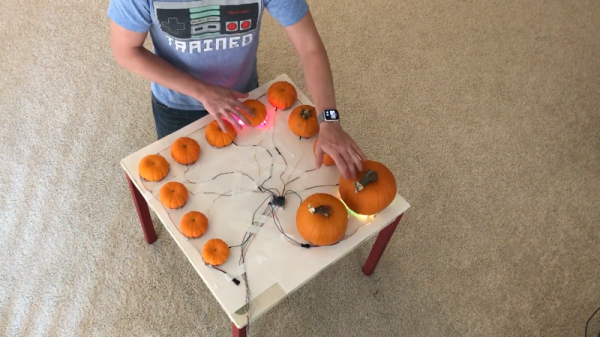

Ever wanted to build a touch table or other touch-input project, but got stuck figuring out the ‘touch’ part? [Jean Perardel] has your back with his multi-touch frame over on IO that makes any surface touch-reactive. In [Jean]’s case, that surface is ultimately a TV inside of a table.

Of course, it’s a bit of a misnomer to say the surface itself becomes touch-reactive. What’s really happening here is that [Jean] is using light triangulation to detect shadows and determine the coordinates of the shadow-casting object. Many barcode scanners and consumer-level document scanners use a contact image sensor (CIS) to detect objects in the path of IR LEDs. These are a low-power, lower-resolution alternative to the CCDs found in high-grade scanners.

As [Jean] explains in the video below, an object placed in the path of a single IR LED facing a sensor array of either type will block the light from reaching the sensors. Keep adding LEDs and their emission angles will begin to overlap, increasing the detection precision. [Jean] reverse engineered a couple of different types of scanners until he found a suitable one. He ended up with CIS that has 2700 light sensors lined up in the space of 20cm (7.87″).

[Jean] designed a 3D-printable frame to hold 96 IR LEDs in stacks of three. A Teensy turns on the LEDs, detects the touch event, calculates the position, and sends those coordinates to a Pi to be displayed on the screen. He eventually went wireless and then built a nice looking touch table to house a 32″ TV.

This is not the only way to build a multi-touch table, nor is it the simplest. Here’s one that uses finger presses to scatter light and an industrial strength projection-based table that was open-sourced a few years ago.