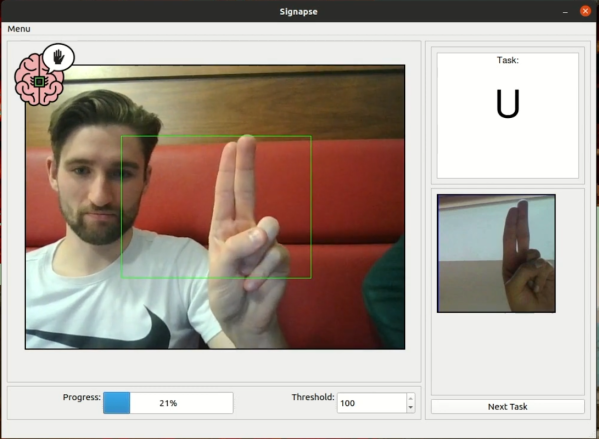

Learning a new language is a great way to exercise the mind and learn about different cultures, and it’s great to have a native speaker around to improve the learning experience. Without one it’s still possible to learn via videos, books, and software though. The task does get much more complicated when trying to learn a language that isn’t spoken, though, like American Sign Language. This project allows users to learn the ASL alphabet with the help of computer vision and some machine learning algorithms.

The build uses a computer vision model in MobileNetV2 which is trained for each sign in the ASL alphabet. A sign is shown to the user on a screen, and the user needs to demonstrate the sign to the computer in order to progress. To do this, OpenCV running on a Raspberry Pi with a PiCamera is used to analyze the frames of the user in real-time. The user is shown pictures of the correct sign, and is rewarded when the correct sign is made.

While this only works for alphabet signs in ASL currently, the team at the University of Glasgow that built this project is planning on expanding it to include other signs as well. We have seen other machines built to teach ASL in the past, like this one which relies on a specialized glove rather than computer vision.