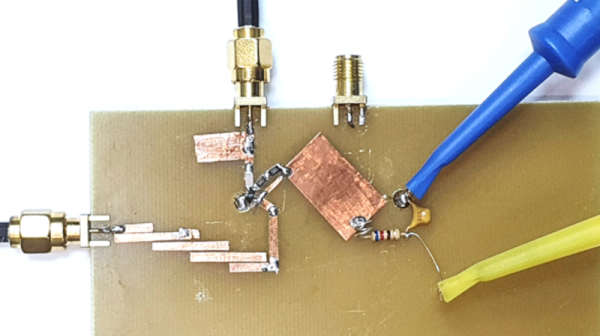

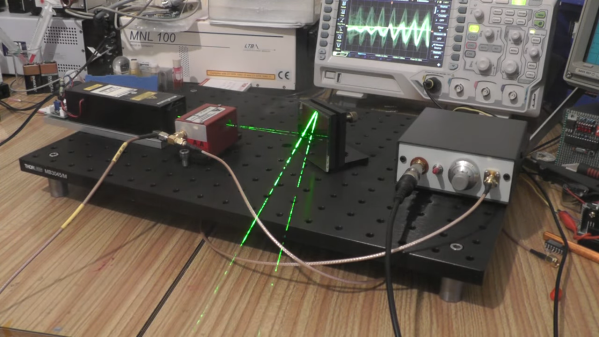

It is an age-old problem. You have a 2.5 GHz source and you want it at 5 GHz. You need a frequency doubler. [All Electronics Channel] has an interesting video that talks not only about the theory of such a device but shows a practical one made with copper strips on a blank PCB substrate.

A fun thing about microwaves is that even little strips of copper are circuit elements since the wavelength at 2.5 GHz is only 12cm. That means a quarter-wave stub is only 3 cm — just over an inch.

The construction technique used is simple and, as he points out, experimenting with a real circuit will give you much more feel for how these circuits work than just reading and working out the math.

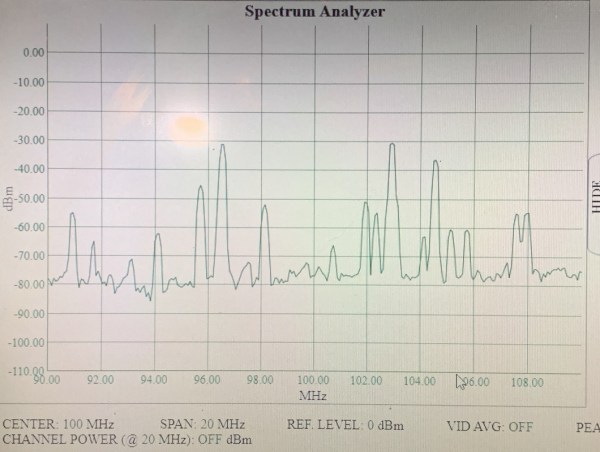

The multiplier drives an amplifier into nonlinearity which, of course, generates harmonics. Then a bandpass filter selects the second harmonic. If you haven’t dealt with stub circuits before, you might want to read up on how a piece of copper connected at one end can act like an inductor, a capacitor, or even a tuned circuit.

If you want more detail on the copper tape technique, we can help. If you don’t want to double frequency, maybe you would prefer to try voltage.