Logarithms are a common idea today, even though we don’t use them as often as we used to. After all, one of the major uses of logarithms is to simplify computations, and computers do that just fine (although they might use logs internally). But 400 years ago, doing math was painful. Enter Joost Bürgi. According to [Welch Labs], his book of mathematical tables should have changed math forever. But it didn’t.

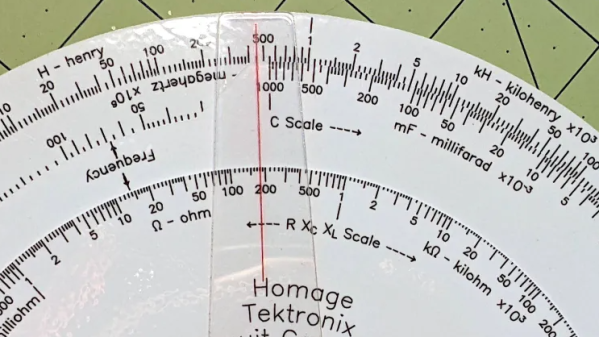

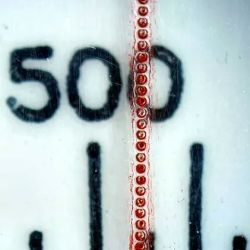

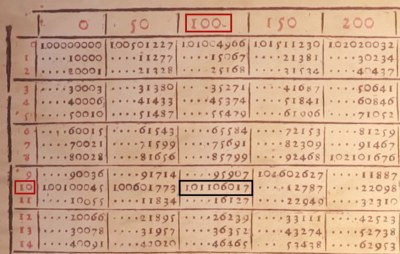

If you know how a slide rule works, you’ll find you already know much of what the video shows. The clockmaker was one of the people who worked out how logs could simplify many difficult equations. He created a table of 23,030 “red and black” numbers to nine digits. Essentially, this was a table of logarithms to a very unusual base: 1.0001.

Why such a strange base? Because it allowed interpolation to a higher accuracy than using a larger base. Red numbers are, of course, the logarithms, and the black numbers are antilogs. The real tables are a bit hard to read because he omitted digits that didn’t change and scaled parts of it by ten (which was changed in the video below to simplify things). It doesn’t help, either, that decimal points hadn’t been invented yet.

Why such a strange base? Because it allowed interpolation to a higher accuracy than using a larger base. Red numbers are, of course, the logarithms, and the black numbers are antilogs. The real tables are a bit hard to read because he omitted digits that didn’t change and scaled parts of it by ten (which was changed in the video below to simplify things). It doesn’t help, either, that decimal points hadn’t been invented yet.

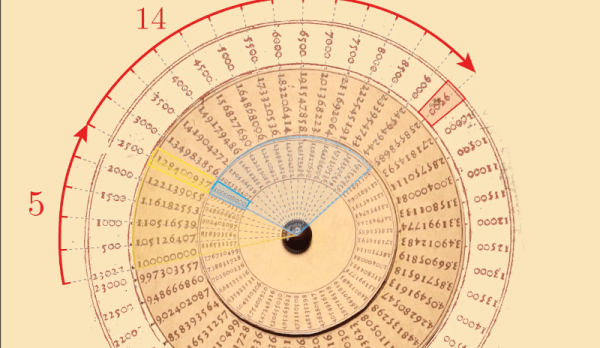

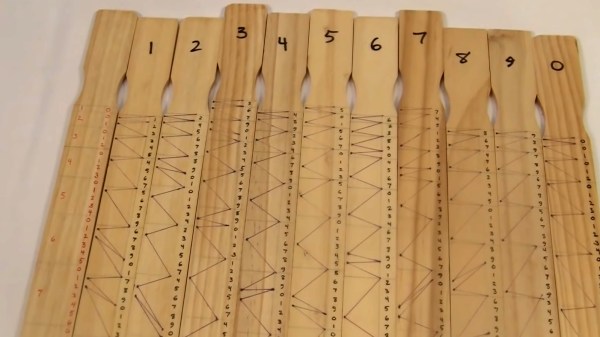

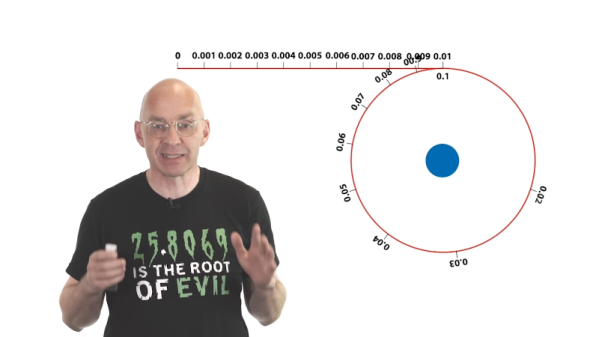

What was really impressive, though, was the disk-like construct on the cover of the book. Although it wasn’t mentioned in the text, it is clear this was meant to allow you to build a circular slide rule, which [Welch Labs] does and demonstrates in the video.

Unfortunately, the book was not widely known and Napier gets the credit for inventing and popularizing logarithms. Napier published in 1614 while Joost published in 1620. However, both men likely had their tables in some form much earlier. However, Kepler knew of the Bürgi tables as early as 1610 and was dismayed that they were not published.

While we enjoy all kinds of retrocomputers, the slide rule may be the original. Want to make your own circular version? You don’t need to find a copy of this book.