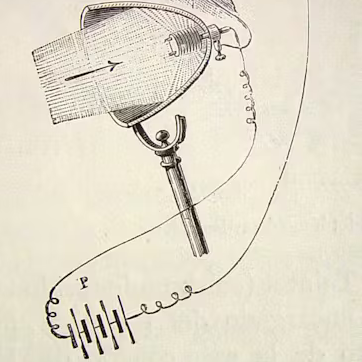

The hoverboard, one of the teen crazes of the last decade, is both a marvel of technology and a source of hacker parts that have appeared in so many projects on these pages. It contains an accelerometer or similar, along with a microcontroller and a pair of motor controllers to drive its in-wheel motors. That recipe is open to interpretation of course and we’ve seen a few in our time, but perhaps not quite like this steampunk design from [Skrubis]. It claims a hoverboard design with no modern electronics, only relays, mercury switches, and neon bulbs.

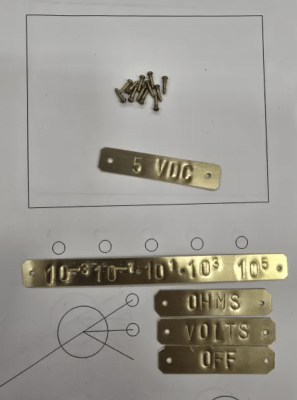

The idea is that it’s a hoverboard from 1884 using parts available in that era, hence there’s talk of telegraph relays and galvanomic piles. The write-up is presented in steampunk-style language which if we’re honest makes our brain hurt, but the premise is intriguing enough to persevere. As far as we can see it uses a pair of relays and a transformer to make an oscillator, from which can be derived the drive for a 3-phase motor. This drive is sent to the motors by further relays operating under the influence of mercury tilt switches.

There are a full set of hardware designs once you wade past the language, but as yet it has no evidence of a prototype. We admit we kinda want it to work because the idea is preposterous enough to be cool if it ran, but we’d be lying if we said we didn’t harbor some doubts. Perhaps you our readers can deliver a verdict, after all presenting you with entertainment is what it’s all about. If a working prototype surfaces we’ll definitely be featuring it, after all it would be cool as heck.

Oddly this isn’t the first non-computerized balance transport we’ve seen.

Featured image: Simakovarik, CC BY-SA 4.0.