We’re not sure what to make of this one. With the variety of smartwatches and fitness trackers out there, we can’t be surprised by what sort of hardware ends up strapped to wrists these days. So a watch with an RPN calculator isn’t too much of a stretch. But adding a hex editor? And a disassembler? Oh, and while you’re at it, a transceiver for the 70cm ham band? Now that’s something you don’t see every day.

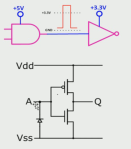

The mind boggles at not only the technical prowess needed to pull off what [Travis Goodspeed (KK4VCZ)] calls the GoodWatch, but at the thought process that led to all these features being packed into the case of a Casio calculator watch. But a lot of hacking is more about the “Why not?” than the “Why?”, and when you start looking at the feature set of the CC430F6137 microcontroller [Travis] chose, things start to make sense. The chip has a built-in RF subsystem, intended no doubt to enable wireless sensor designs. The GoodWatch20 puts the transceiver to work in the 430-MHz band, implementing a simple low-power (QRP) beacon. But the real story here is in the hacks [Travis] used to pull this off, like using flecks of Post-It notes to probe the LCD connections, and that he managed to stay within the confines of the original case.

There’s some real skill here, and it makes for an interesting read. And since the GoodWatch is powered by a coin cell, we think it’d be a great entry for our Coin Cell Challenge contest.

[via r/AmateurRadio]