When you have a bunch of people gathered around a table for a “Dungeons & Dragons” session, you have to expect that things are not always going to go smoothly. After all, people who willingly create and immerse themselves in an alternate reality where one bad roll of the dice can lead to the virtual death of a character they’ve spent months or years with can be traumatic. And with that trauma comes the search for the guilty — it’s the dice! It’s always the dice!

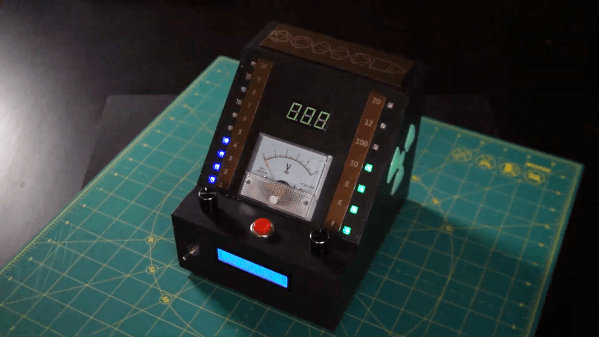

Eliminating that excuse, or at least making it statistically implausible, is the idea behind this radioactively random dice roller. It comes to us from [Science Shack] and uses radioactive decay to generate truly random numbers, as opposed to the pseudorandom number generators baked into most microcontrollers. The design is based on [AlphaPhoenix]’s muon-powered RNG, but with a significant twist: rather than depending on background radiation, [Science Shack] brought the power of uranium to the party.

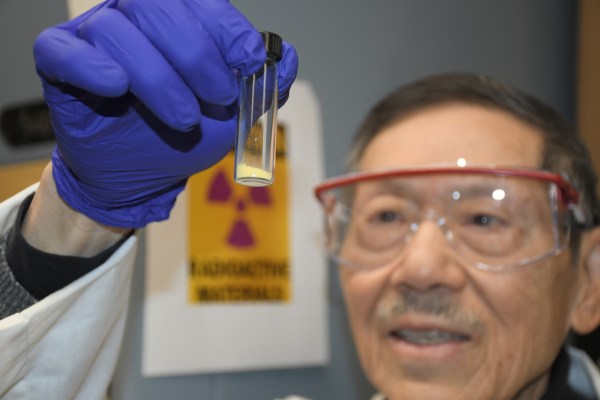

They obtained a sample of autunite, a weird-looking phosphate mineral that contains a decent amount of uranium, perfect for stimulating the Geiger counter built into the dice roller. Autunite also has the advantage of looking very cool under UV light, taking on a ghostly “fuel rod glow,” in the [Homer Simpson] sense. The decay-powered RNG at the heart of this build is used to simulate throws of every standard D&D die, from a D4 to a D100. The laser-cut hardboard case holds all the controls and displays, and also has some strategically placed openings to gaze upon its glowing guts.

We really like the design, but we have to quibble with the handling of the uranium ore; true, the specific activity of autunite is probably pretty low, but it seems like at least some gloves would have been in order.

Continue reading “Roll The Radioactive Dice For Truly Random D&D Play”