We’ll admit we’ve kicked around the idea of a camera that digitally signs a picture so you could prove it hasn’t been altered and things like the time and place the photo was taken for years. Apparently, products are starting to hit the market, and Spectrum reports on a Leica that, though it will set you back nearly $10,000, can produce pictures with cryptographic signatures.

This isn’t something Leica made up. In 2019, a consortium known as the Content Authenticity Initiative set out to establish a standard for this sort of thing. The founders are no surprise: The New York Times, Adobe, and Twitter. There are 200 companies involved now, although Twitter — now X — has left.

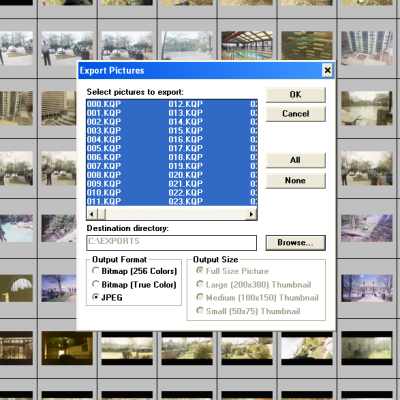

The problem, the post notes, is that software support is limited. There are only a few programs that recognize and process digital signatures. That’ll change, of course, and — we imagine — if you needed to prove the provenance of a photo in court, you’d just buy the right software you needed.

We haven’t dug into the technology, but presumably keeping the private key secure will be very important. The consortium is clear that the technology is not about managing rights, and it is possible to label a picture anonymously. The signature can identify if an image was taken with a camera or generated by AI and details about how it was taken. It also can detect any attempt to tamper with the image. Compliant programs can make modifications, but they will be traceable through the cryptographic record.

Will it work? Probably. Can it be broken? We don’t know, but we wouldn’t bet that it couldn’t without a lot more reading. PDF signatures can be hacked. Our experience is that not much is truly unhackable.