Readers of a certain vintage no doubt have pleasant memories of drive-in theaters, and we are chuffed to see that a few hundred of these cinematic institutions endure today. While most theaters broadcast the audio on an FM station these days, the choice is still yours to use the chunky, often crackly speaker that attaches to the car window.

Seeking to relive the drive-in audio experience at home, [codemakesitgo] picked up a drive-in theater speaker on eBay and turned it into a Bluetooth device that sounds much better than it did in its weather-beaten days outside.

Seeking to relive the drive-in audio experience at home, [codemakesitgo] picked up a drive-in theater speaker on eBay and turned it into a Bluetooth device that sounds much better than it did in its weather-beaten days outside.

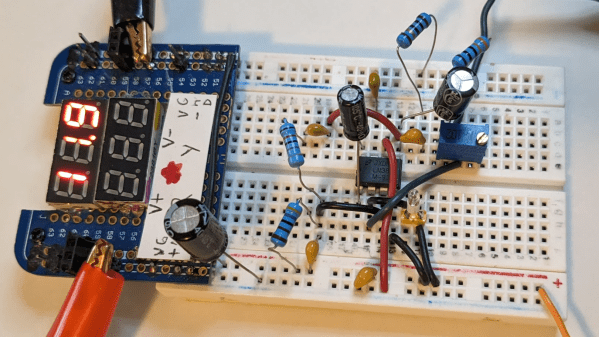

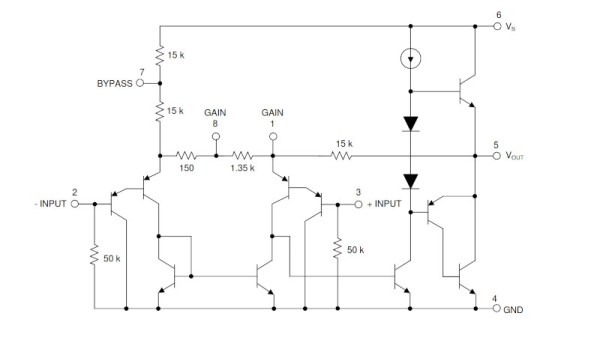

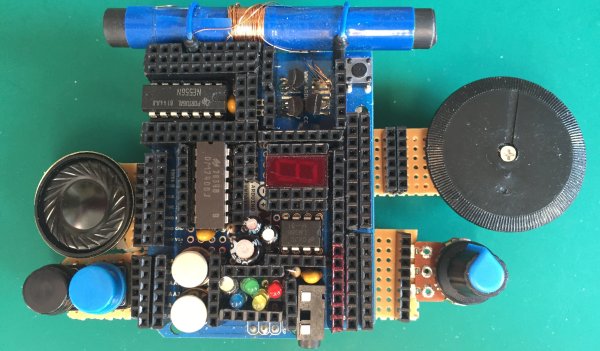

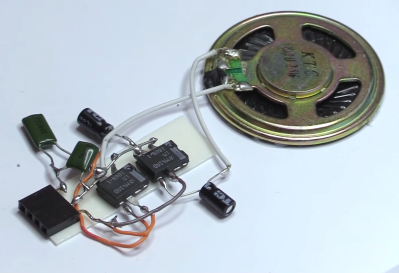

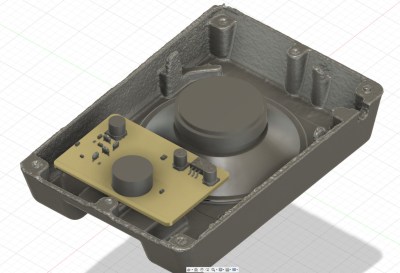

There isn’t a whole lot to this build — it’s essentially a new speaker cone, a Bluetooth receiver, an amp, and a battery. The real story is in the way that [codemakesitgo] uses Fusion360 to bring it all together.

After 3D scanning the case, [codemakesitgo] made sure each piece would fit, using a custom-built model of the new speaker and a 3D model of a custom PCB. Good thing, too, because there is barely enough clearance for the speaker. Be sure to check out the brief demo video after the break.

Continue reading “A 360° View Of A Classic Drive-In Speaker”