For humans, moving our arms and hands onto an object to pick it up is pretty easy; but for manipulators, it’s a different story. Once we’ve found the object we want our robot to pick up, we still need to plan a path from our robot hand to the object all the while lugging the remaining limbs along for the ride without snagging them on any incoming obstacles. The space of all possible joint configurations is called the “joint configuration space.” Planning a collision-free path through them is called path planning, and it’s a tricky one to solve quickly in the world of robotics.

These days, roboticists have nailed out a few algorithms, but executing them takes 100s of milliseconds to compute. The result? Robots spend most of their time “thinking” about moving, rather than executing the actual move.

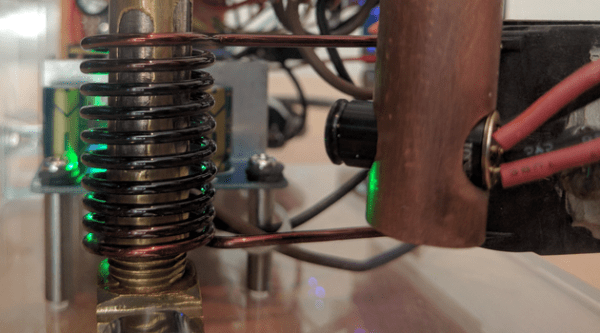

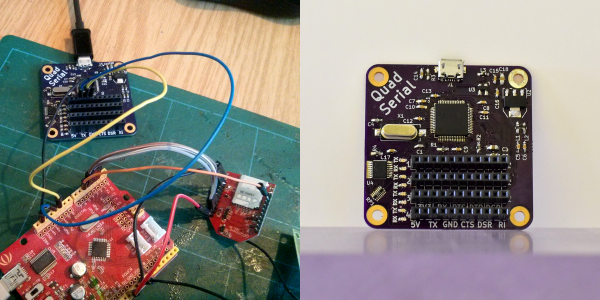

Robots have been lurching along pretty slowly for a while until recently when researchers at Duke University [PDF] pushed much of the computation to hardware on an FPGA. The result? Path planning in hardware with a 6-degree-of-freedom arm takes under a millisecond to compute!

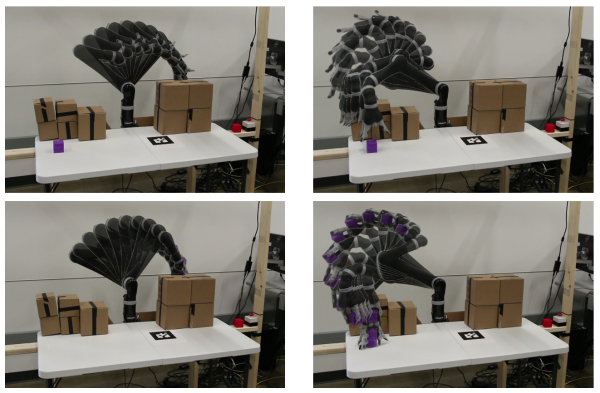

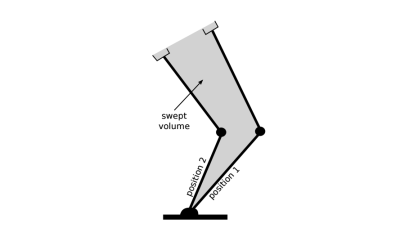

It’s worth asking: why is this problem so hard? How did hardware make it faster? There’s a few layers here, but it’s worth investigating the big ones. Planning a path from point A to point B usually happens probabilistically (randomly iterating to the finishing point), and if there exists a path, the algorithm will find it. The issue, however, arises when we need to lug our remaining limbs through the space to reach that object. This feature is called the swept volume, and it’s the entire shape that our ‘bot limbs envelope while getting from A to B. This is not just a collision-free path for the hand, but for the entire set of joints.

Encoding a map on a computer is done by discretizing the space into a sufficient resolution of 3D voxels. If a voxel is occupied by an obstacle, it gets one state. If it’s not occupied, it gets another. To compute whether or not a path is OK, a set of voxels that represent the swept volume needs to be compared against the voxels that represent the environment. Here’s where the FPGA kicks in with the speed bump. With the hardware implementation, voxel occupation is encoded in bits, and the entire volume calculation is done in parallel. Nifty to have custom hardware for this, right?

We applaud the folks at Duke University for getting this up-and-running, and we can’t wait to see custom “robot path-planning chips” hit the market some day. For now, though, if you’d like to sink your teeth into seeing how FPGAs can parallelize conventional algorithms, check out our linear-time sorting feature from a few months back.

Continue reading “Manipulators Get A 1000x FPGA-based Speed Bump”