Did you know Hackaday is hosting a fantastic contest to build hardware and software? It’s true! The Hackaday Prize will award hundreds of thousands of dollars to Hackaday community members for building the coolest hardware designed to make a difference in the world.

The Hackaday Prize has many ways to enter, focusing on several themes throughout this year. We’ll be discussing that and opening the floor to questions. Tomorrow, Friday, April 28, at noon, Pacific time, we’re hosting a Hack Chat for the Hackaday Prize over on Hackaday.io.

Our guest host for this chat is [Alberto], creator of the project that won last year’s Hackaday Prize. He’ll be in the Hack Chat telling everyone what he learned from last year’s Hackaday Prize. If we’re lucky, he might even tell us something about what building his project out in the Supply Frame Design Lab is like. It’s all very cool, and it’s going down tomorrow at noon, PDT.

Here’s How To Take Part:

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging.

Our Hack Chats are live community events on the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging.

Log into Hackaday.io, visit that page, and look for the ‘Join this Project’ Button. Once you’re part of the project, the button will change to ‘Team Messaging’, which takes you directly to the Hack Chat.

You don’t have to wait until tomorrow; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.

And Tindie, Too!

Next Tuesday, we’re going to have another chat geared toward sellers on Tindie, the online marketplace where anyone can buy or sell DIY hardware.

Next Tuesday, we’re going to have another chat geared toward sellers on Tindie, the online marketplace where anyone can buy or sell DIY hardware.

This time around, we’re talking about Kickstarter. We roped [Zach Dunham] into this one. He’s the Design & Technology Outreach Lead at Kickstarter, and by every measure a really cool guy.

[Zach] will discuss the ins and outs of turning a hardware project into a Kickstarter campaign. Surprisingly, there’s a significant overlap between Tindie sellers and Kickstarter — some sellers test their ideas on Tindie and build up to doing a crowd funding campaign. Others complete a campaign and then come over to Tindie to sell excess inventory or second runs. Either way, there’s a great opportunity for market verification or simply getting your gear into the hands of those who want to use it.

If you want to get in on the Kickstarter chat action, head on over to the Tindie Dog Park. Request to join the project and show up in the chat sometime before 1pm Pacific on Tuesday, May 2.

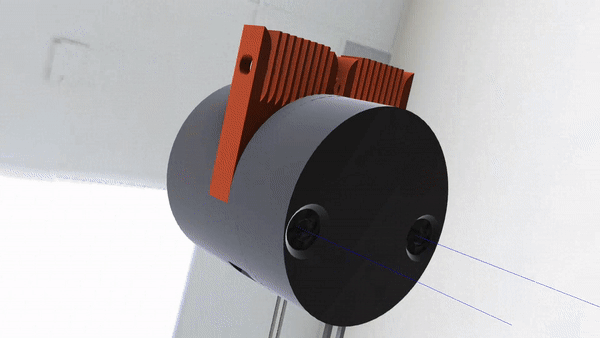

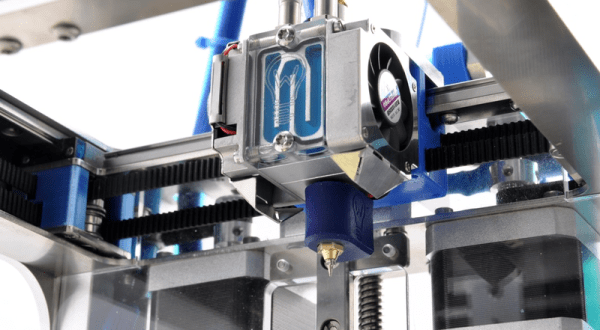

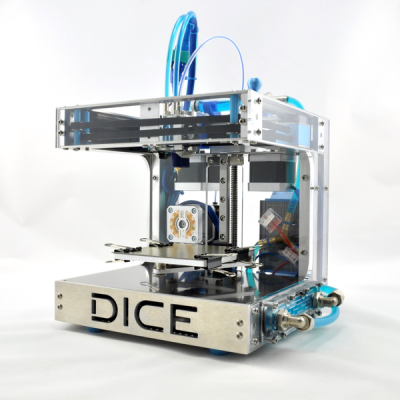

[René] had built a few 3D printers before, so he had a good feel for the parameters and design tradeoffs before he embarked on the DICE project. Making a small print volume, for instance, means that the frame can be smaller and thus exponentially more rigid. This means that it’s capable of very fast movements — 833 mm/s is no joke! It also looks to make very precise little prints. What could make it even more awesome? Water-cooled stepper motors, magnetic interchangeable printheads, and in-built lighting.

[René] had built a few 3D printers before, so he had a good feel for the parameters and design tradeoffs before he embarked on the DICE project. Making a small print volume, for instance, means that the frame can be smaller and thus exponentially more rigid. This means that it’s capable of very fast movements — 833 mm/s is no joke! It also looks to make very precise little prints. What could make it even more awesome? Water-cooled stepper motors, magnetic interchangeable printheads, and in-built lighting.