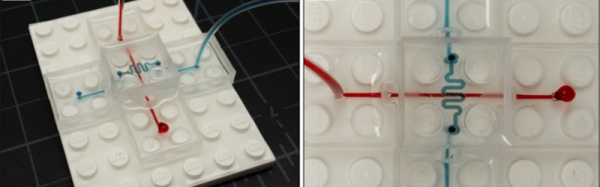

Some of us have looked at clear resin jewelry casting kits online and started to get ideas. Hackaday’s own [Nava Whiteford] decided to take the plunge and share the results. After purchasing a reasonably economical clear resin jewelry casting kit from eBay, a simple trial run consisted of embedding a solar lantern into some of the clear resin to see how it turned out. The results were crude, but promising. A short video overview is embedded below.

Some of us have looked at clear resin jewelry casting kits online and started to get ideas. Hackaday’s own [Nava Whiteford] decided to take the plunge and share the results. After purchasing a reasonably economical clear resin jewelry casting kit from eBay, a simple trial run consisted of embedding a solar lantern into some of the clear resin to see how it turned out. The results were crude, but promising. A short video overview is embedded below.

The big hangup was lack of a proper mold. [Nava]’s attempt to use a plastic bag and a cup as an expedient stand-in for a proper mold was not without its flaws, and the cup needed to be broken before the cured resin could be removed. Despite this, the results were good; the mixing needed careful measurement and the curing process was lengthy but the cured resin is as attractive as the advertisements promise. Mixing introduced many air bubbles into the mixture, but most of them seemed to disappear on their own during the curing process. The results of this quick test may not be pretty, but the resin seems to have held up its end of the bargain and delivered the expected smooth, clear finish.

Continue reading “Using A Jewelry Kit To Resin-Encase Electronics”