Like many of us who fiddle with microcontrollers, [Mike] and [Brian] often found themselves using an ISP programmer and a USB-to-serial adapter. But when they started working on the latest generation of ATtiny chips, they found themselves in need of a Unified Program, and Debug Interface (UPDI) programmer as well. So they decided to wrap all three functions into one handy open hardware gadget.

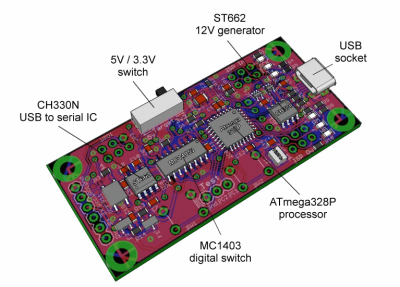

They call their creation the AVR General Purpose Programmer, or AVRgpp for short. It runs on an ATmega328P with a Pro Mini bootloader, which means that the programmer itself is fully compatible with the Arduino IDE. USB-to-serial capability is provided by a CH330N, and a MC14053 digital switch IC is used to select between talking to the AVRgpp’s onboard MCU or the target device.

They call their creation the AVR General Purpose Programmer, or AVRgpp for short. It runs on an ATmega328P with a Pro Mini bootloader, which means that the programmer itself is fully compatible with the Arduino IDE. USB-to-serial capability is provided by a CH330N, and a MC14053 digital switch IC is used to select between talking to the AVRgpp’s onboard MCU or the target device.

A 128 x 32 I2C OLED and two push buttons are used to select the device’s current mode, and there’s a physical switch to select between 5 V or 3.3 V power for the target. There’s also a ST662 12 V regulator, as UPDI targets occasionally need a high voltage pulse to switch into programming mode. Everything is packaged up in a pocket-sized laser cut enclosure that you can easily toss in your bag.

[Mike] and [Brian] say they are considering putting the AVRgpp into small scale production if there’s enough interest, so let them know if you’d like to get one without having to build it yourself.