Modern home cinema equipment is well-equipped with features for interoperability and convenience, but in practice, competing standards and arcana can make it fall over. Sometimes, you’ve gotta do a little work on your own to glue it all together, and that’s what led [Victor] to develop a little utility of his own.

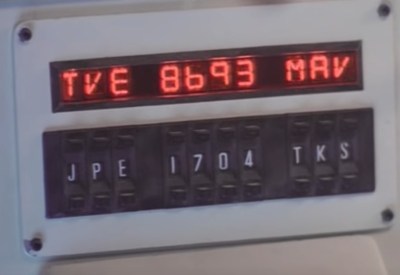

ChromecastControls is a tool that makes controlling your home cinema easier by improving Chromecast’s integration with the CEC features of HDMI. CEC, or Consumer Electronics Control, is a bidirectional serial bus that is integrated as a part of the HDMI standard. It’s designed to help TVs, audio systems, and other AV hardware to communicate, and allow the user to control an entire home cinema setup with a single remote. Common use cases are TVs that send shutdown commands to attached soundbars when switched off, or Blu-Ray players that switch the TV on to the correct output when the play button is pressed.

[Victor]’s tool allows Chromecast to pass volume commands to surround sound processors, something that normally requires the user to manually adjust their settings with a separate remote. It also sends shutdown commands to the attached TV when Chromecast goes into its idle state, saving energy. It relies on the PyChromecast library to intercept traffic on the network, and thus send the appropriate commands to other hardware. Simply running the code on a Raspberry Pi that’s hooked up to any HDMI port on a relevant device should enable the CEC commands to get through.

It’s a project that you might find handy, particularly if you’re sick of leaving your television on 24 hours a day because Chromecast never bothered to implement a simple CEC command on an idle timeout. CEC hacks have a long history, too – we’ve been covering them as far back as 2010!