“How’s the weather?” is a common enough question down here on the ground, but it’s even more important to pilots. Even if they might not physically be in the cockpit of the craft they are flying. [Justin Parsons] explains how weather affects drone flights and how having API access to micro weather data can help ensure safe operations.

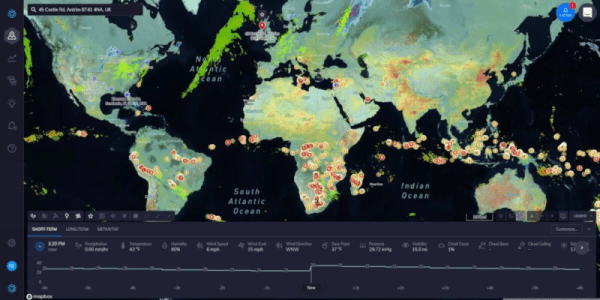

As drone capability and flight time increase, the missions they will fly are getting more and more complex. [Justin] uses a service called ClimaCell which has real-time, forecast, and historical weather data available across the globe. The service isn’t totally free, but if you make fewer than 1,000 calls a day you might be able to use a developer account which doesn’t cost anything.

According to [Justin], weather data can help with pre-flight planning, in-flight operations, and post-flight analysis. The value of accurate forecasting is indisputable. However, a drone or its ground controller could certainly understand real-time weather in a variety of ways and record it for later use, so the other two use cases maybe a little less valuable.

While on the subject, it seems to us that accurate forecasting could be important for other kinds of projects. Will you have enough sun to catch a charge on your robot lawnmower tomorrow? If your beach kiosk is expecting rain, it could deploy an umbrella or close some doors and shutdown for a bit.

If you insist on using a free service, the ClimaCell blog actually lists their top 8 APIs. Naturally, their service is number one, but they do have an assessment of others that seems fair enough. Nearly all of these will have some cost if you use it enough, but many of them are pretty reasonable unless you’re making a huge number of calls.

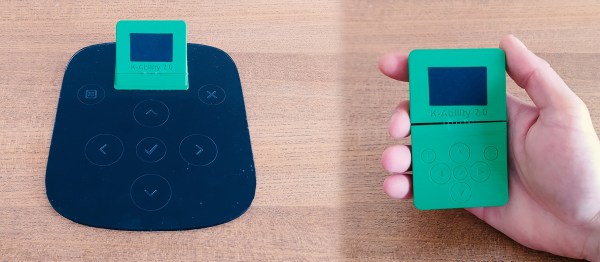

How would you use accurate micro weather data? Let us know in the comments. Then again, sometimes you want to know the weather right from your couch. Or maybe you’d like your umbrella to tell you how long the storm is going to last.