For hackers, cheap (and arguably disposable) consumer hardware makes for a ready supply of free or low-cost components. When you can walk into a big box store and pick up a new low-end laptop for $150, how many are going to spend the money to repair or upgrade the one they have now? So the old ones go to the bin, or get sold online for parts. From an ecological standpoint our disposable society is terrible, but at least we get some tech bargains out of the deal.

Case in point, the dirt cheap 32 GB eMMC SSDs [Jason Gin] recently scored. Used by Hewlett Packard on their line of budget laptops, he was able to snap up some of these custom drives for only $12 each. Only problem was, since they were designed for a very specific market and use case, they aren’t exactly the kind of thing you can just slap in your computer’s drive bay. He had to do some reverse engineering to figure out how to talk to them, and then some impressive fine-pitch soldering to get them plugged in, but in the end he got some very handy drives for an exceptionally low price.

Case in point, the dirt cheap 32 GB eMMC SSDs [Jason Gin] recently scored. Used by Hewlett Packard on their line of budget laptops, he was able to snap up some of these custom drives for only $12 each. Only problem was, since they were designed for a very specific market and use case, they aren’t exactly the kind of thing you can just slap in your computer’s drive bay. He had to do some reverse engineering to figure out how to talk to them, and then some impressive fine-pitch soldering to get them plugged in, but in the end he got some very handy drives for an exceptionally low price.

[Jason] starts by figuring out the drive’s pinout using the cornerstone of the hacker’s electronic toolkit: the multimeter. By putting one lead on an obvious ground point such as the PCB’s screw holes, you can work through the pins on the connector and make some educated guesses as to what’s what. Ground pins will read as a short, but the meter should read power and data pins as a forward-biased diode. With a rough idea of the pin’s identities and some luck, he was able to figure out that it was basically a standard SATA connection in a different form factor.

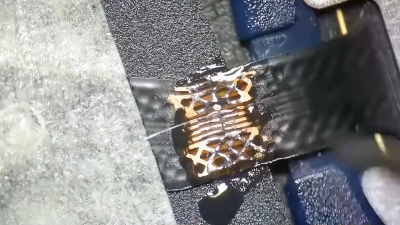

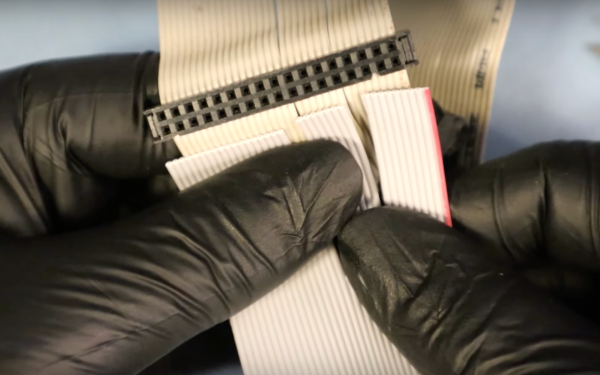

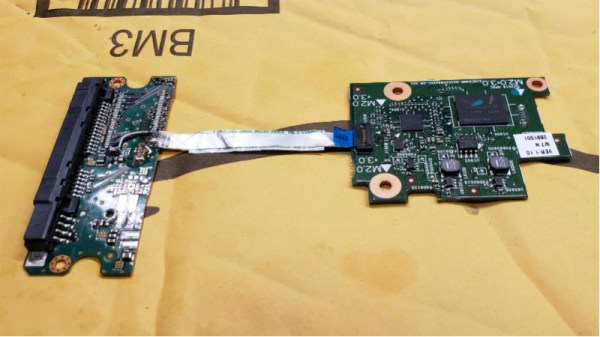

To actually hook it up to his computer, he pulled the PCB off of a dead SATA hard drive, cut it down to size, and was able to use fine magnet wire to attach the conductors in the drive’s ribbon cable to the appropriate pads. He sealed everything up with a healthy dose of hot glue to make sure it didn’t pull loose, and then ran some drive diagnostics on his cobbled together SSD to make sure it was behaving properly. [Jason] reports the drive isn’t exactly a speed demon, but given the low cost and decent performance he still thinks it’s worth the work to use them for testing out different operating systems and the like.

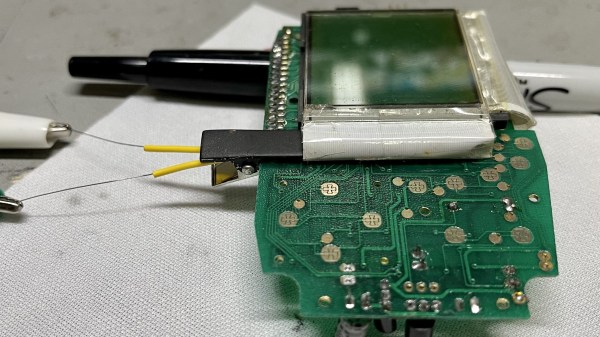

[Jason] seems to have something of an obsession with eMMC hacking. Last time we heard from him, he was bringing a cheap Windows tablet back from the dead by replacing its shot eMMC chip.