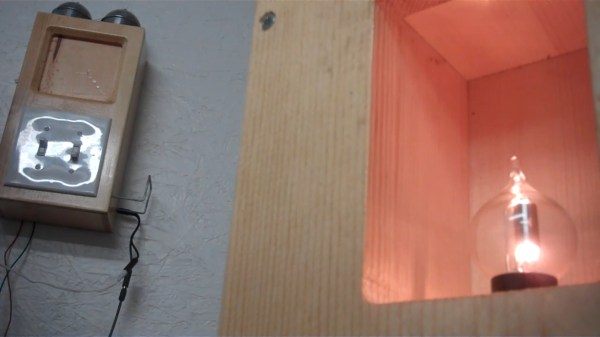

Hot on the heels of their carbon microphone build a few years ago, [Simplifier] strung up a two-phone network between the house and the workshop. Both telephones are completely DIY except for the pair of switches on the front. Each side has a bell, a microphone, and an audio transformer. Listening is done through a pair of headphones, and both users speak through a homebrew carbon microphone.

We particularly love the bell, which is made from fence post caps. Sitting between the bells and ready to strike is a ball bearing mounted on a really thick piece of wire that’s driven by an electromagnet. To make a call, you use both switches — the one on the left pulls either the bell or the microphone to ground, while the switch on the

We particularly love the bell, which is made from fence post caps. Sitting between the bells and ready to strike is a ball bearing mounted on a really thick piece of wire that’s driven by an electromagnet. To make a call, you use both switches — the one on the left pulls either the bell or the microphone to ground, while the switch on the left right is used momentarily to send 6 V from the lantern battery down the 50 ft. line to the other phone to ring it. You’ll see what we mean in the demo video after the break. Check out the sound of those fence post caps!

[Simplifier] wound an audio transformer that provides the necessary impedance matching to use regular headphones as receivers. Since the homebrew microphones only need 1.5 V, [Simplifier] split the voltage across two carbon contacts placed in series. That’s still more than necessary, but [Simplifier] was able to make it work.

More recently, [Simplifier] has built a beautiful and even better carbon microphone and even hosted a back-to-basics Hack Chat.

Continue reading “The Calls Are Coming From Inside The House (or Workshop)”