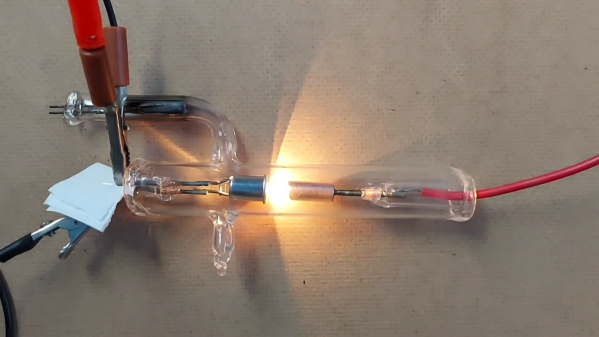

We recently ran an article on a sweet percussion device made by minimal-hardware-synth-madman [Gijs Gieskes]. Basically, it amplifies up an analog meter movement and plays it by slamming it into the end stops. Rhythmically, and in stereo. It’s got that lovely thud, plus the ringing of the springs. It takes what is normally a sign that something’s horribly wrong and makes a soundtrack out of it. I love it.

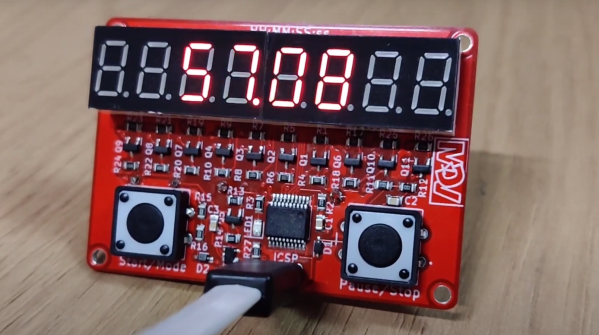

[Gijs] has been making electro-mechanical musical hacks for about as long as I’ve been reading Hackaday, if not longer. We’ve written up no fewer than 22 of his projects, and the first one on record is from 2005: an LSDJ-based hardware sequencer. All of his projects are simple, but each one has a tremendously clever idea at its core that comes from a deep appreciation of everything going on around us. Have you noticed that VU meters make a particular twang when they hit the walls? Sure you have. Have you built a percussion instrument out of it? [Gijs] has!

Maybe it’s a small realization, and it’s not going to change the world by itself, but I’ve rebuilt more than a couple projects from [Gijs]’ repertoire, and each one has made my life more fun. And if you’re a regular Hackaday reader, you’ve probably seen hundreds or thousands of similar little awesome ideas played out, and maybe even taken some of them on as your own as well. When they accumulate up, I believe they can change the world, at least in the sense of filling up a geek’s life. I hope that feeling comes across when we write up a project. Those of you out there hacking, we salute you!