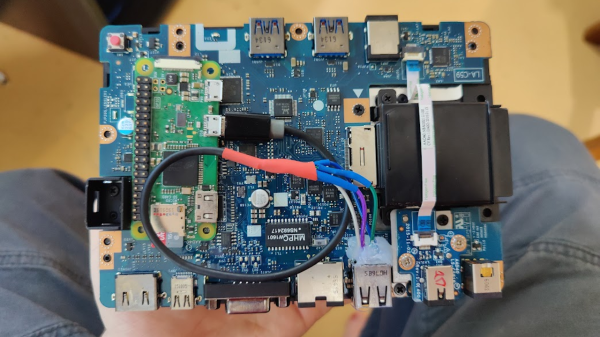

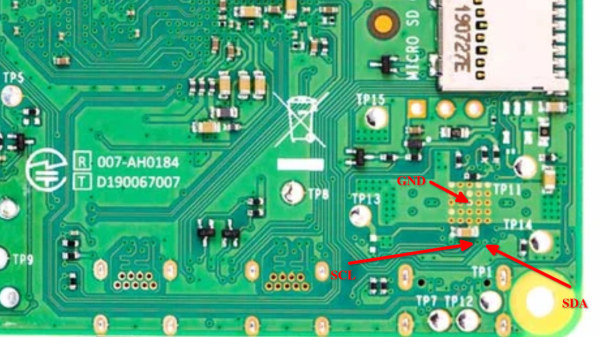

In today’s installment of Betteridge’s law enforcement, here’s an evil USB-C dock proof-of-concept by [Lachlan Davidson] from [Aura Division]. We’ve seen malicious USB devices aplenty, from cables and chargers to flash drives and even suspicious USB fans. But a dock, however, is new. The gist is simple — you take a stock dock, find a Pi Zero W and wire it up to a USB 2.0 port tapped somewhere inside the dock. Finding a Pi Zero is unquestionably the hardest part in this endeavor — on the software side, everything is ready for you, just flash an SD card with a pre-cooked malicious image and go!

On the surface level, this might seem like a cookie-cutter malicious USB attack. However, there’s a non-technical element to it; USB-C docks are becoming more and more popular, and with the unique level of convenience they provide, the “plug it in” temptation is much higher than with other devices. For instance, in shared workspaces, having a USB-C cable with charging and sometimes even a second monitor is becoming a norm. If you use USB-C day-to-day, the convenience of just plugging a USB-C cable into your laptop becomes too good to pass up on.

This hack doesn’t exactly use any USB-C specific technical features, like Power Delivery (PD) – it’s more about exploiting the convenience factor of USB-C that incentivizes you to plug a USB-C cable in, amplifying an old attack. Now, BadUSB with its keystroke injection is no longer the limit — with a Thunderbolt-capable USB-C dock, you can connect a PCIe device to it internally and even get access to a laptop’s RAM contents. Of course, fearing USB-C cables is not a viable approach, so perhaps it’s time for us to start protecting from BadUSB attacks on the software side.