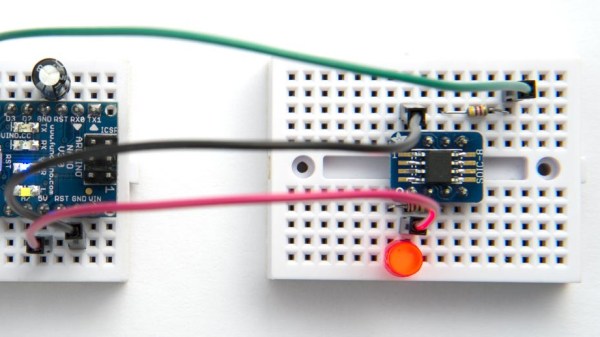

Cryptographic coprocessors are nice, for the most part. These are small chips you connect over I2C or One-Wire, with a whole bunch of cryptographic features implemented. They can hash data, securely store an encryption key and do internal encryption/decryption with it, sign data or validate signatures, and generate decent random numbers – all things that you might not want to do in firmware on your MCU, with the range of attacks you’d have to defend it against. Theoretically, this is great, but that moves the attack to the cryptographic coprocessor.

In this BlackHat presentation (slides), [Olivier Heriveaux] talks about how his team was tasked with investigating the security of the Coldcard cryptocurrency wallet. This wallet stores your private keys inside of an ATECC608A chip, in a secure area only unlocked once you enter your PIN. The team had already encountered the ATECC608A’s predecessor, the ATECC508A, in a different scenario, and that one gave up its secrets eventually. This time, could they break into the vault and leave with a bag full of Bitcoins?

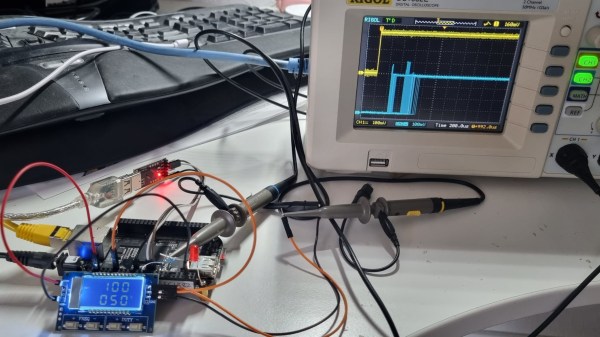

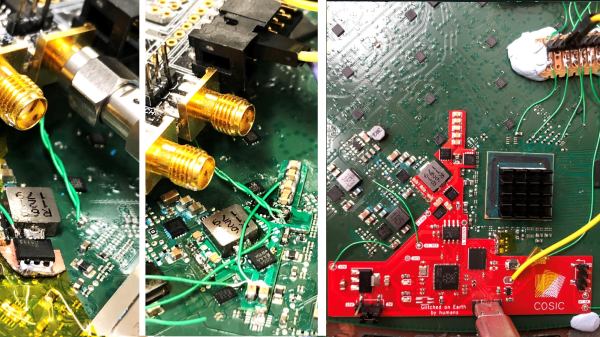

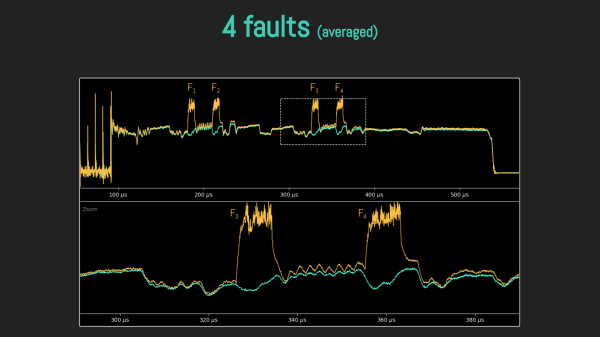

Lacking a vault door to drill, they used a powerful laser, delidding the IC and pulsing different areas of it with the beam. How do you know when exactly to pulse? For that, they took power consumption traces of the chip, which, given enough tries and some signal averaging, let them make educated guesses on how the chip’s firmware went through the unlock command processing stages. We won’t spoil the video for you, but if you’re interested in power analysis and laser glitching, it’s well worth 30 minutes of your time.

You might think it’s good that we have these chips to work with – however, they’re not that hobbyist-friendly, as proper documentation is scarce for security-through-obscurity reasons. Another downside is that, inevitably, we’ll encounter them being used to thwart repair and reverse-engineering. However, if you wanted to explore what a cryptographic coprocessor brings you, you can get an ESP32 module with the ATECC608A inside, we’ve seen this chip put into an IoT-enabled wearable ECG project, and even a Nokia-shell LoRa mesh phone!

Continue reading “Defeating A Cryptoprocessor With Laser Beams” →