[Tim] had a problem with his microwave. The buzzer was exceptionally annoying, and once his hot pockets or pizza rolls were done, the buzzer wouldn’t shut off. A two-kilohertz tone infected his soul. It was the only sound echoing in a Boschian nightmare of reheated frozen food.

Unlike an existential ennui, an annoying buzzer in a microwave is something anyone can fix. [Tim] just took a pair of pliers to the buzzer and ripped it off the PCB. This left him with another problem — how to tell when his food was done. This was solved by putting the Windows XP startup sound in his microwave.

With the buzzer out of the way, [Tim] took an Arduino nano and loaded it up with the Windows XP startup sound. There isn’t much Flash on the Arduino, but it could hold an 18kB sample, enough to play the startup sound at 8kHz. The sound itself is PCM audio and easily stuffed into a sketch.

The Arduino listens for the 2kHz tone generated by the microwave and sends the XP startup sound through a tiny class D amplifier. After mounting a speaker inside the microwave, [Tim] has a very vaporwavemicrowave.

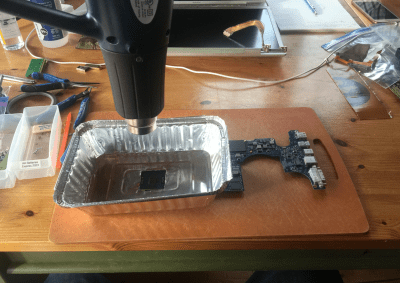

[DocDawning] has a bit of a Mac hoarding problem, and frequently pays $20 for broken laptops of this vintage. Most of the time, the fix is simple: the RAM needs to be reseated, or something like that. Rarely, he comes across a machine that isn’t fixed so easily. The solution, in this case,

[DocDawning] has a bit of a Mac hoarding problem, and frequently pays $20 for broken laptops of this vintage. Most of the time, the fix is simple: the RAM needs to be reseated, or something like that. Rarely, he comes across a machine that isn’t fixed so easily. The solution, in this case,