Electric-assisted bicycles, or ebikes, are fundamentally changing the way people get around cities and towns. What were once sweaty, hilly, or difficult rides have quickly turned into a low-impact and inexpensive ways around town without foregoing all of the benefits of exercise. [Braden] hoped to expand this idea to the open waters and is building what he calls the ebike of kayaking, using the principles of electric-assisted bicycles to build a kayak that helps you get where you’re paddling without removing you completely from the experience.

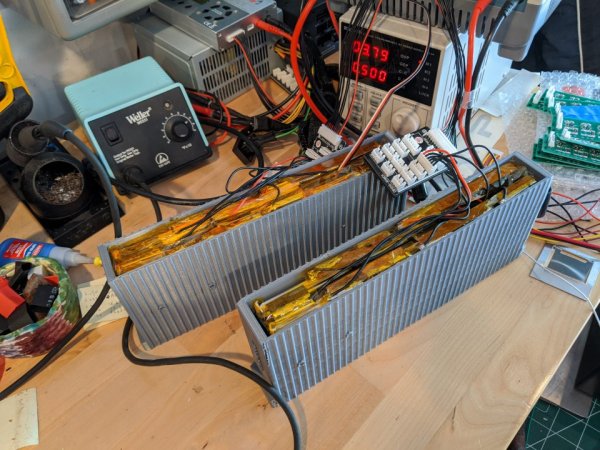

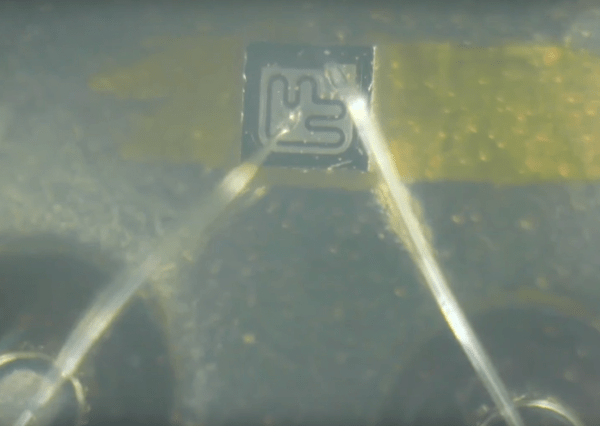

The core of the project is a brushless DC motor originally intended a hydrofoil which is capable of providing 11 pounds (about 5 kg) of thrust. [Braden] has integrated it into a 3D-printed fin which attaches to the bottom of his inflatable kayak. The design of the fin took a few iterations to get right, but with a working motor and fin combination he set about tuning the system’s PID controller in a tub before taking it out to the open water. With just himself, the battery, and the motor controller in the kayak he’s getting about 14 miles of range with plenty of charge left in the battery after the trips.

[Braden]’s plans for developing this project further will eventually include a machine learning algorithm to detect when the rider is paddling and assist them, rather than simply being a throttle-operated motor as it exists currently. On a bicycle, strapping a sensor to the pedals is pretty straightforward, but we expect detecting paddling to be a bit more of a challenge. There are even more details about this build on his personal project blog. We’re looking forward to seeing the next version of the project but if you really need to see more boat hacks in the meantime be sure to check out [saveitforparts]’s boat which foregoes sails in favor of solar panels.

Continue reading “Paddling Help From Electric-Assisted Kayak”