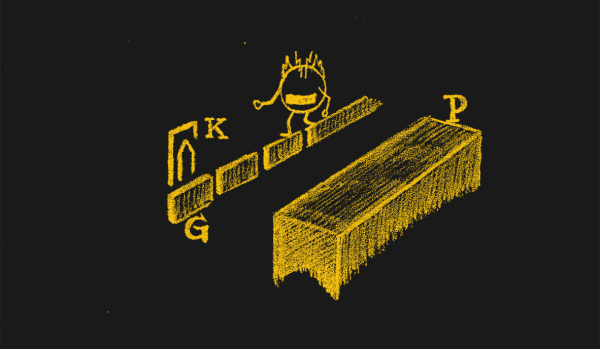

[Miroslav Nemecek] really pushes the limits of the Pico with his PicoVGA project, which packs a surprising number of features. His main goal with this library is to run retro games which can fit within the limited RAM and processing power of the Pico, but the demo video below shows a wide array of potential applications.

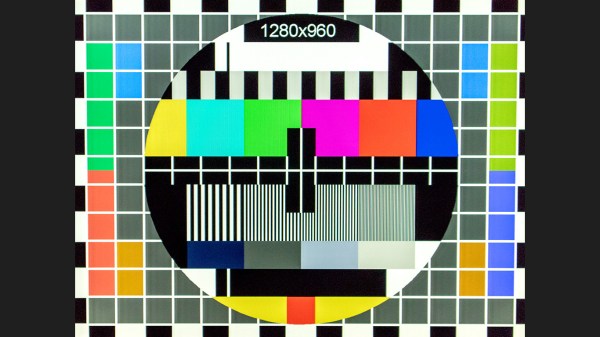

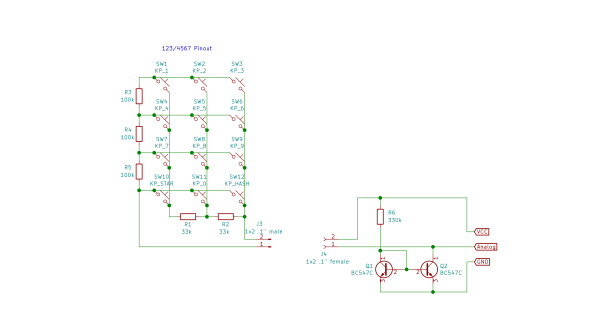

The library provides a whole slew of features, including frame buffering, sprites, overlays, and resolutions up to 1280×960 in either NTSC or PAL timings. A PWM-driven audio output channel is also included in the package. His library takes full advantage of the programmable I/O module functionality and uses the second core which is dedicated to video processing. However, with care, the second core can perform application tasks in certain circumstances. The VGA analog output signals are provided by resistor ladders, and pixel color is 8-bit R3G3B2 format. To be clear, [Miroslav] does cheat a little bit here in one regard — he overclocks the processor up to 270 MHz to meet the timing demands in some of the resolutions.

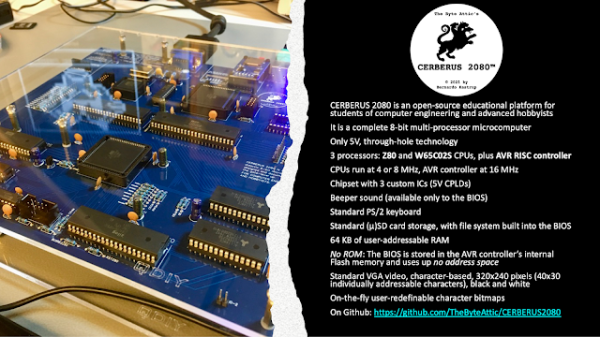

[Miroslav] has developed these tools using ARM-GCC on Windows, but he lacks the experience to make a Linux build. He welcomes help on that front from anyone familiar with Linux. And stay tuned — there may be more coming from [Miroslav] in the future. He notes that the PicoVGA library was created as part of a retro gaming computer project which is still under development. We look forward to hearing more about this when it gets released.

A couple of weeks ago we wrote about a monochrome VGA version of Pong for the Pico by [Nick Bild]. It’s exciting to see these projects which are exploring the limits of the Pico’s capabilities. Have you seen any boundary-pushing applications for the Pico? Let us know in the comments below. Thanks to [Pavel Krivanek] for sending this project to our tip line.