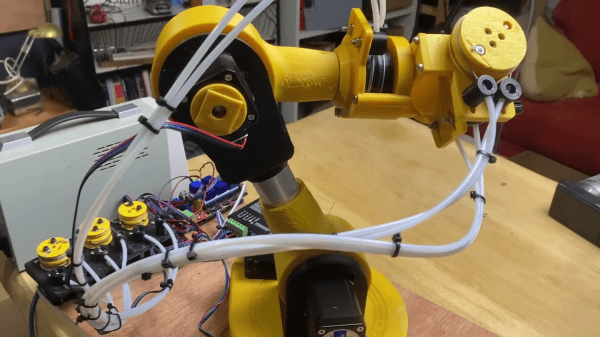

A major challenge of robotic arms is the weight of the actuators, especially closer to the end of the arm. The long lever arm means more torque is required from the other actuators, and everything flexes a bit more. To get around this, [RoTechnic] moved the wrist stepper motors off the arms entirely.

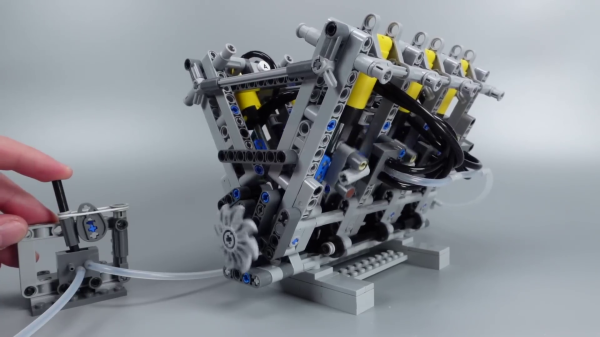

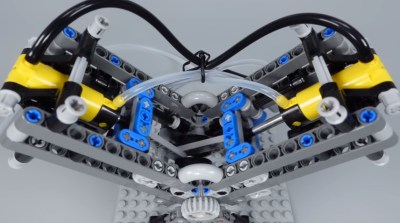

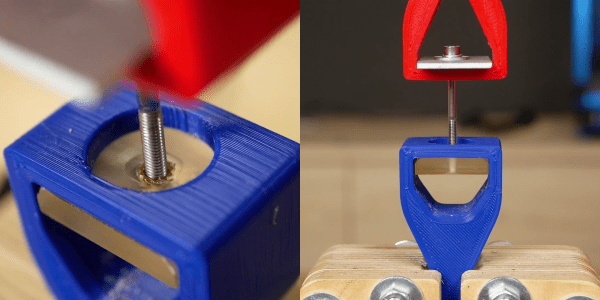

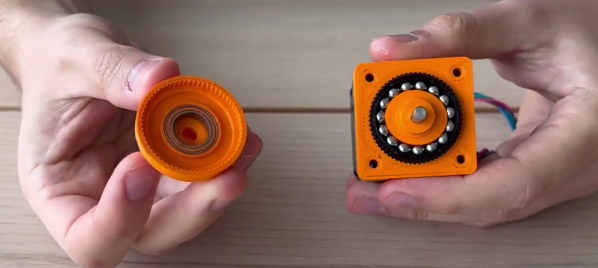

He built a push-pull mechanism that uses braided fishing line to transfer motion to the robot arm’s wrist using Bowden tubes. The motors are mounted on the arm’s base, with a drum and two lengths of fishing line on the shafts. The lines pass through an adjustable tensioner before entering the Bowden tubes. This drum mechanism is also present on each of the three rotating axes of the wrist.

[RoTechnic] used an Arduino-powered RAMPS board as a controller, which is programmed to accept over the serial interface. He created a simple GUI and scripting interface in Jupyter Labs to generate and send command, which seems like an excellent solution for testing.

We can see this mechanism being a useful for a variety of motion applications, and definitely something to add to the idea toolbox. It is somewhat similar to some other cable-operated joints we’ve seen in humanoid robots and other 3D printed arms.

Continue reading “3-DOF Robot Arm Wrist Without The Motor Weight”