It’s always unfortunate to find a FedEx tag on your door saying you missed a delivery; especially when you were home the whole time. After having this problem a few times [Lee] decided to rig up a doorbell notifier for his Android phone.

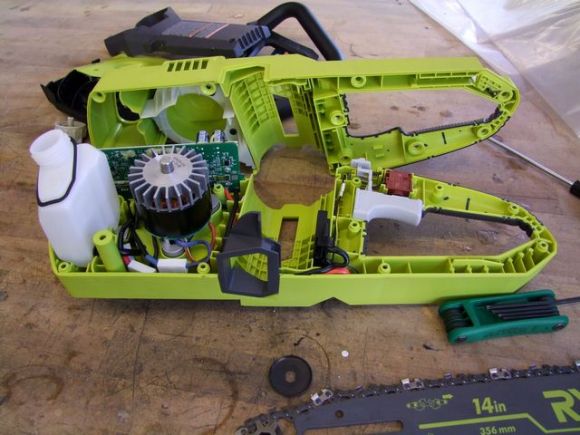

[Lee]’s doorbell uses a 10 VAC supply to ring a chime. To reduce modifications to the doorbell, he added an integrated rectifier and a PNP transistor. The rectifier drives the transistor when the bell rings, and pulls a line to ground.

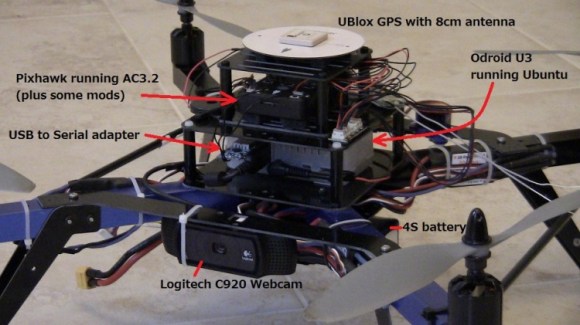

An old Netgear router running OpenWRT senses this on a GPIO pin. Hotplugd is used to run a script when the button push is detected.

The software is discussed in a separate post. The router runs a simple UDP server written in C. The phone polls this server periodically using SL4A: a Python scripting layer for the Android platform. To put it all together, hotplugd sends a UNIX signal to the UDP server when the doorbell is pushed. Once the phone polls the server a notification will appear, and [Lee] can pick up his package without delay.