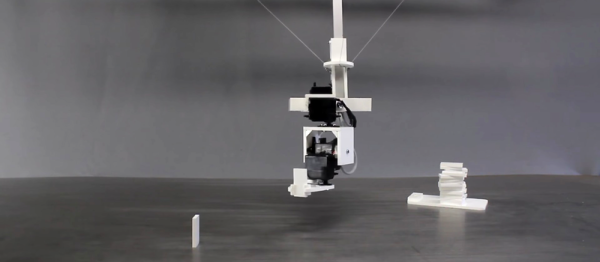

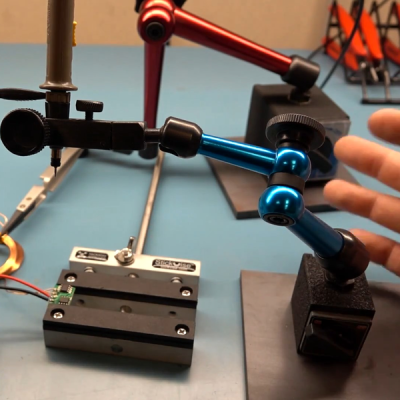

[ProtoG] sent us in this video (also below) where he demonstrates the use of machinist’s dial-gauge indicator arms as helping hands. I’ll admit that I got so jealous that I ordered a pair. I wouldn’t say that I need more tools to hold things in place, but I certainly want them. The rapid coarse placement combined with fine adjustment looks so sweet. Using them as scope-probe holders is brilliant.

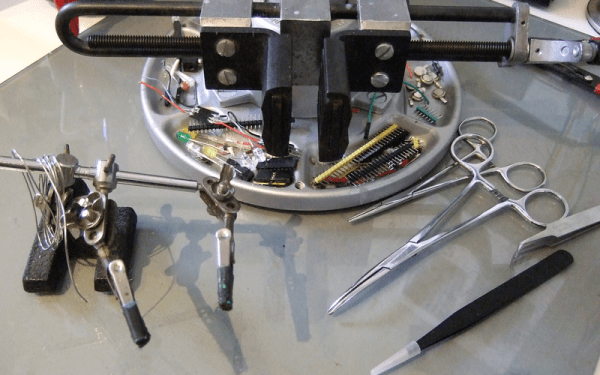

Our own helping hands, purchased for $5 from a surplus shop, have seen nearly twenty years of use now. About ten years ago, I heat-shrinked and plasti-dipped the jaws, and since then they do less damage to cable insulation. The clips kept coming loose, but that was fixed with a little epoxy. I never used the magnifying glass, and by removing it I bought some more sliding room for the jaws, which was an easy win. The base has a “non-slip” coating of Shoe-Goo that keeps it in place on the desk. Cork might be classier.

Our own helping hands, purchased for $5 from a surplus shop, have seen nearly twenty years of use now. About ten years ago, I heat-shrinked and plasti-dipped the jaws, and since then they do less damage to cable insulation. The clips kept coming loose, but that was fixed with a little epoxy. I never used the magnifying glass, and by removing it I bought some more sliding room for the jaws, which was an easy win. The base has a “non-slip” coating of Shoe-Goo that keeps it in place on the desk. Cork might be classier.

For bigger holding, there’s always the desk vise, though I’ll admit that I mostly use it for holding PCBs while soldering, and that a better solution for that particular task wouldn’t hurt. [Mike Szczys] tells me that the Stickvise seen here is a handy thing to have on the bench. It started on Hackaday.io and we still carry it in the store.

For grabbing the fiddly little things, nothing beats a pair of hemostats and a range of tweezers. Hemostats in the desk vise make a great ad hoc holder. Good sharp tweezers pay for themselves with the first removed splinter, or placing SMT parts.

So, Hackaday, what do you use for holding things? What do you hold your PCBs with while soldering? What do you use to hold down SMD parts? What’s your third hand, or twenty-third? Continue reading “Ask Hackaday: Helping Hands”