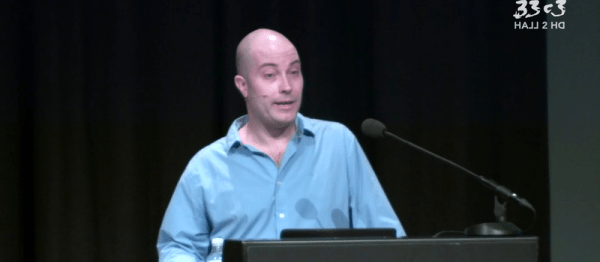

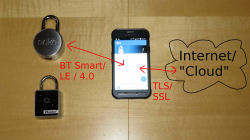

Fast-forward to the end of the talk, and you’ll hear someone in the audience ask [Ray] “Are there any Bluetooth locks that you can recommend?” and he gets to answer “nope, not really.” (If this counts as a spoiler for a talk about the security of three IoT locks at a hacker conference, you need to get out more.)

Unlocking a padlock with your cellphone isn’t as crazy as it sounds. The promise of Internet-enabled locks is that they can allow people one-time use or limited access to physical spaces, as easily as sending them an e-mail. Unfortunately, it also opens up additional attack surfaces. Lock making goes from being a skill that involves clever mechanical design and metallurgy, to encryption and secure protocols.

Unlocking a padlock with your cellphone isn’t as crazy as it sounds. The promise of Internet-enabled locks is that they can allow people one-time use or limited access to physical spaces, as easily as sending them an e-mail. Unfortunately, it also opens up additional attack surfaces. Lock making goes from being a skill that involves clever mechanical design and metallurgy, to encryption and secure protocols.

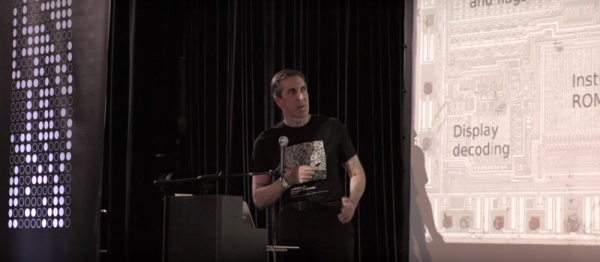

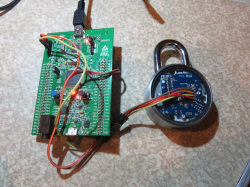

In this fun talk, [Ray] looks at three “IoT” locks. One, he throws out on mechanical grounds once he’s gotten it open — it’s a $100 lock that’s as easily shimmable as that $4 padlock on your gym locker. The other, a Master lock, has a new version of a 2012 vulnerability that [Ray] pointed out to Master: if you move a magnet around the outside the lock, it actuates the motor within, unlocking it. The third, made by Kickstarter company Noke, was at least physically secure, but fell prey to an insecure key exchange protocol.

In this fun talk, [Ray] looks at three “IoT” locks. One, he throws out on mechanical grounds once he’s gotten it open — it’s a $100 lock that’s as easily shimmable as that $4 padlock on your gym locker. The other, a Master lock, has a new version of a 2012 vulnerability that [Ray] pointed out to Master: if you move a magnet around the outside the lock, it actuates the motor within, unlocking it. The third, made by Kickstarter company Noke, was at least physically secure, but fell prey to an insecure key exchange protocol.

Along the way, you’ll get some advice on how to quickly and easily audit your own IoT devices. That’s worth the price of admission even if you like your keys made out of metal instead of bits. And one of the more refreshing points, given the hype of some IoT security talks these days, was the nuanced approach that [Ray] took toward what counts as a security problem because it’s exploitable by someone else, rather than vectors that are only “exploitable” by the device’s owner. We like to think of those as customization options.