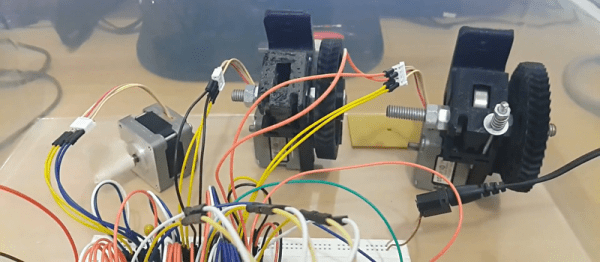

What can’t the little $5 WiFi module do? Now that [lhartmann] has got an ESP8266 controlling the motors of a 3D printer, that’s one more item to check off the list.

What’s coolest about this project is the way that [lhartmann] does it. The tiny ESP8266 has nowhere near the required number of GPIO pins, the primary SPI is connected to the onboard flash memory, and the secondary SPI is poorly documented and almost nobody uses it. So, [lhartmann] chose to use the I2S outputs.

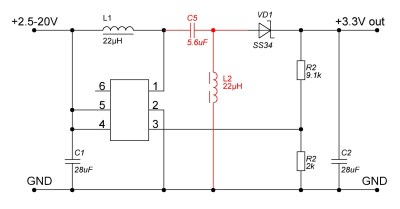

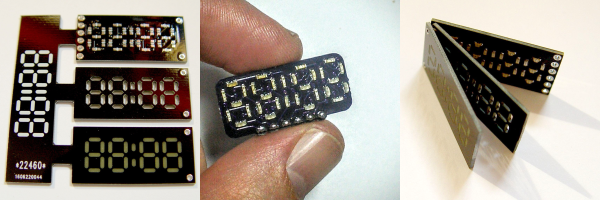

I2S is most often an audio protocol, so this might at first seem like a strange choice. Although I2S sounds like I2C, it’s really essentially an SPI protocol with a fourth wire that alternates to designate the right or left channel. It’s actually just perfect for sending 16×2 bits of data at high data rates.

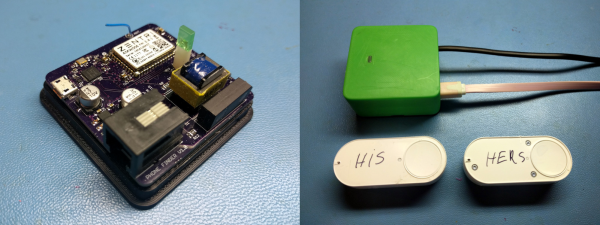

[lhartmann] takes these 32 bits and feeds them into four shift registers, producing 32 outputs from just the four I2S data lines. That’s more than enough signals to run the stepper motors. And since it updates at 192 kHz sample rate, it’s plenty fast enough to drive them.

The other side benefit of this technique is that it can work on single-board computers with just a little bit of software. Programming very complicated stepper movements then becomes just a matter of generating the right “audio” file and playing it out. [lhartmann] demonstrated this earlier with an Orange Pi. That’s pretty cool, too.

The code for turning the ESP8266 and a short handful of 74HC595s into a 3D printer controller are up on GitHub, so go check it out.

Thanks [CNLohr] for the tip!