Reading Hackaday is great! You get so many useful tips from watching other people work, it’s truly changed nearly everything about the way I hack, especially considering that I’ve been reading Hackaday for the past 15 years. Ideas, freely shared among peers, are the best of the free and open-source hardware community. But there’s a dark downside: I’m going CNC mill shopping.

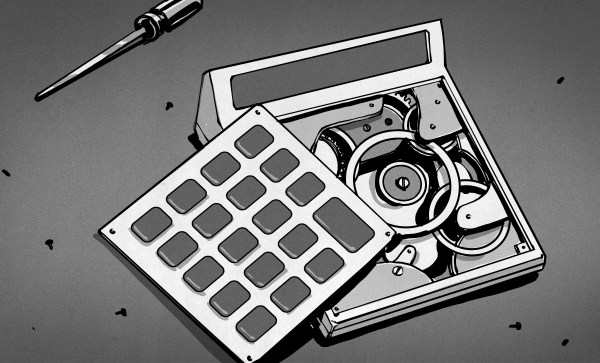

It all started with [Robin]’s excellent video and website tutorial on his particular PCB DIY procedures. You see, I love making PCBs at home, because I’m unafraid of chemistry, practiced with a rolling pin and iron, and super-duper impatient. If I can get a board done today, I’m not waiting a week, even if that means an hour of work on my part.

Among other things, he’s got this great technique with a scriber pen and a cleverly designed registration base that make it easy for him to do nearly perfectly aligned two-sided boards with a resolution approaching etching. The ability to make easy double-sided boards, with holes drilled, makes milling attractive, but the low resolution of v-cutter milled boards has been the show-stopper for me. If that’s gone, maybe it’s time to take a serious look.

Among other things, he’s got this great technique with a scriber pen and a cleverly designed registration base that make it easy for him to do nearly perfectly aligned two-sided boards with a resolution approaching etching. The ability to make easy double-sided boards, with holes drilled, makes milling attractive, but the low resolution of v-cutter milled boards has been the show-stopper for me. If that’s gone, maybe it’s time to take a serious look.

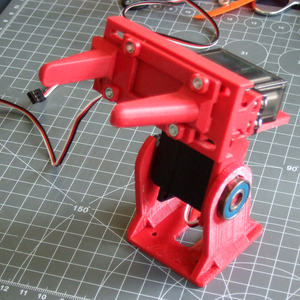

And heck, making PCBs is really just the tip of the iceberg for what I’d want to do with a CNC mill. Currently, I do dodgy metalworking with an x-y table and a drill press, some of which may someday land me in the hospital. But if I had a mill, I’d be doing all sorts of funny wood joinery and who knows what else. I lack experience with a mill, but coincidentally, we just had a Hack Chat on Linux for machine tools this week. You see? It’s all conspiring against me.

The only question left is what I should get. I’m looking at the ballscrew 3040 range of CNCs, and maybe upgrading the spindle. I’d like to mill up to aluminum, but don’t really need steel. What do you think?

Both the takedown notice and counter-notice are binding legal documents, sworn under oath of perjury. Notices and counter-notices can be used or abused, and copyright law is famously full of grey zones. The nice thing about GitHub is that they publish all DMCA notices and counter-notices they receive, so

Both the takedown notice and counter-notice are binding legal documents, sworn under oath of perjury. Notices and counter-notices can be used or abused, and copyright law is famously full of grey zones. The nice thing about GitHub is that they publish all DMCA notices and counter-notices they receive, so