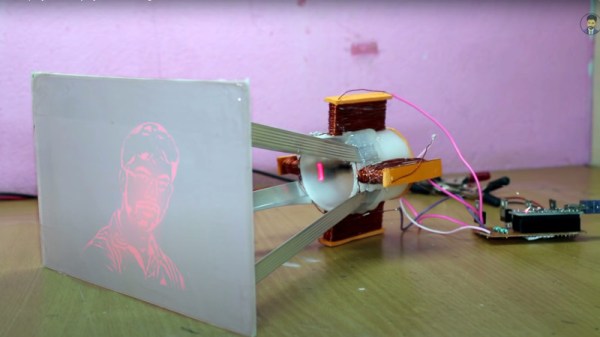

Update 6/23/21: Many people have called this out as fake. When viewed at 1/4 speed, you can see the logos in the YouTube video are always full-off or full-on and never caught mid way through a scanned frame. The images may be projected from off-camera to the left, rather than by the diode behind the screen. It’s a neat idea, but on closer review the demo provided smells a bit fishy so we’ve added a “Real or Fake” tag and updated the title. Update #2: [Kanti Sharma] wrote into the tipsline apologizing for the faked video, saying that he tried to get it to work but couldn’t and then “used a phone and a lens to fake the laser”. Thanks for fessing up to this one.

There are some times when an awesome project comes into your feed, but a language barrier intervenes as you try to follow its creator’s description. [Kanti Sharma]’s laser display appears to be a fantastic piece of work, but YouTube’s automatic translations in the video below make so little sense as to leave us Anglophones none the wiser as to what he’s saying. The principle comes across without need for translation though: he’s taken a laser diode module and is using it to create a vector scan by mounting it in the middle of a set of coils driven through beefy FETs by an Arduino. It’s an electromagnetic take on the same principle used in a CRT vector displays such as the famous Vectrex console, with the beam of electrons replaced with laser light.

It’s a technique not unlike what’s been used for years in the lighting industry, in which much larger laser displays are created with mirrors mounted on galvanometers. There must be a physical limit at which the weight of the laser slows down the movement, but if the video is to be believed it’s certainly capable of displaying graphics on a screen.

People have done a lot of things with lasers on these pages, but there have been surprisingly few vector displays using them. Here’s one from nearly a decade ago.

Continue reading “Fake: A Laser Display Board Of Your Very Own”

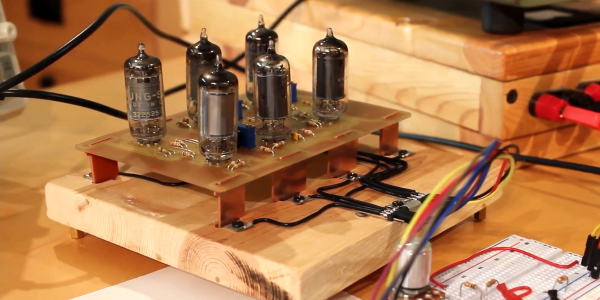

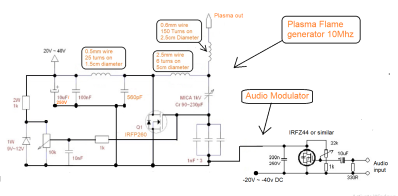

A look at the circuit diagram and construction will probably elicit the response from most of you that it looks a lot like a Tesla coil, and in fact that’s exactly what it is without the usual large capacitor “hat” on top. This arrangement has been used for commercial plasma tweeters using both tubes and semiconductors, and differs somewhat from the singing Tesla coils you may have seen giving live performances in that it’s designed to maintain a consistent small volume of discharge rather than a spectacular lightning show to thrill an audience.

A look at the circuit diagram and construction will probably elicit the response from most of you that it looks a lot like a Tesla coil, and in fact that’s exactly what it is without the usual large capacitor “hat” on top. This arrangement has been used for commercial plasma tweeters using both tubes and semiconductors, and differs somewhat from the singing Tesla coils you may have seen giving live performances in that it’s designed to maintain a consistent small volume of discharge rather than a spectacular lightning show to thrill an audience.