Software-defined radios or SDRs have provided a step-change in the way we use radio. From your FM broadcast receiver which very likely now has single-application SDR technology embedded in a chip through to the all-singing-all-dancing general purpose SDR you’d find on an experimenter’s bench, control over signal processing has moved from the analogue domain into the digital. The possibilities are limitless, and some of the old ways of building a radio now seem antiquated.

[Pete Juliano N6QW] is an expert radio home-brewer of very long standing, and he’s proved there’s plenty of scope for old-fashioned radio homebrewing in an SDR with his RADIG project. It’s an SDR transceiver for HF which does all the work of quadrature splitting and mixing with homebrewed modules rather than the more usual technique of hiding it in an SDR chip. It’s a very long read in a diary format from the bottom up, and what’s remarkable is that he’s gone from idea to working SDR over the space of about three weeks.

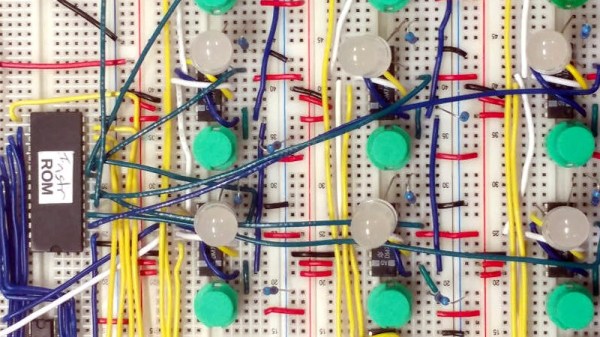

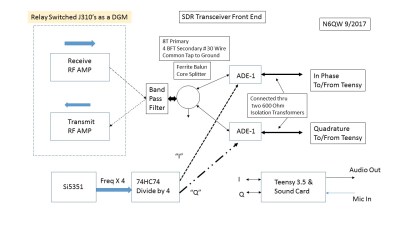

So what goes into a homebrew SDR? Both RF preamplifier, filters, and PA are conventional as you might expect, switched between transmit and receive with relays. A common transmit and receive signal path is split into two and fed to a pair of ADE-1 mixers where they are mixed with quadrature local oscillator signals to produce I and Q that is fed to (or from in the case of transmit) a StarTech sound card. The local oscillator is an Si5351 synthesiser chip in the form of an SDR-Kits USB-driven module, and the 90 degree phased quadrature signals are generated with a set of 74AC74 flip-flops as a divider.

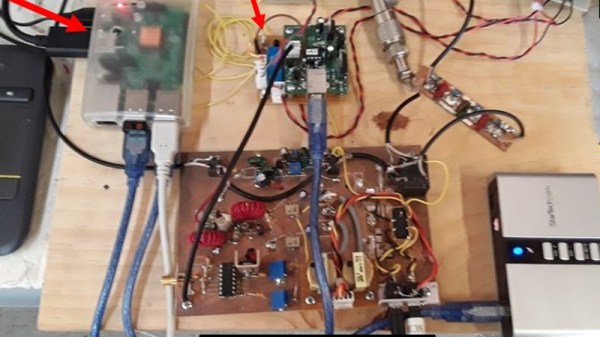

Running the show is a Raspberry Pi running Quisk, and though he mentions using a Teensy to control the Si5351 at the start of his diary it seems from the pictures of the final radio that the Pi has taken on that work. It’s clear that this is very much an experimental radio as it stands with wired-together modules on a wooden board, so we look forward to whatever refinements will come. This has the feel of a design that could eventually be built by many other radio amateurs, so it’s fascinating to be in at the start.

If I and Q leave you gasping when it comes to SDR technology, maybe we can help.

Thanks [Bill Meara N2CQR] for the tip!