Switch-mode power supplies are ubiquitous. Standard off-the-shelf modules in a consistent range of form factors available from multiple manufacturers. Globalized manufacturing and trade has turned them from expensive devices into commodity parts, and they long ago replaced iron-cored transformers as the go-to choice when a high-current low-voltage mains supply is required.

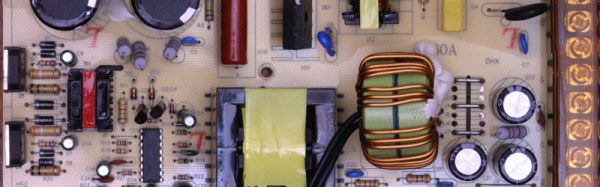

[Lindsay Wilson] faced a power supply problem for a motor he was working with, it required 7.4V and no off-the-shelf power supplies were to be found with that voltage. His solution was to take a 12V supply and modify it to deliver a variable voltage so he could dial in his requirement. A Chinese-made 12v 33A switch-mode supply was purchased, and he set to work.

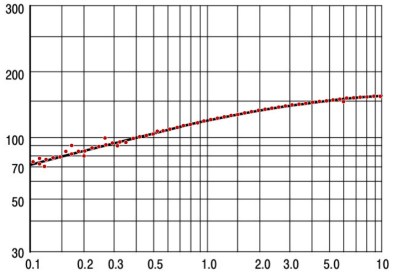

In the event he was able to design a replacement feedback divider incorporating a rotary potentiometer, and achieve a voltage range of 5 to 15V. A small LED voltmeter mounted next to it in the PSU case gave him a very neat result.

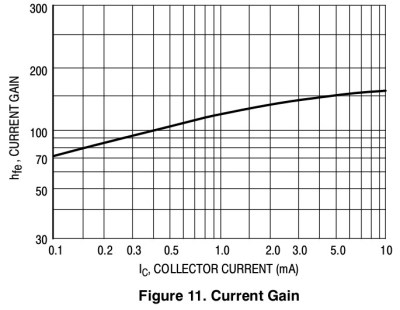

Modifying a switch-mode supply to deliver a different voltage is a well-worn path we’ve covered at least once before. What makes Lindsay’s article worth a read is his reverse-engineering and examination in detail of the PSU circuit. If you’d like to learn more about all the different facets of design that go into a switch-mode PSU, it’s a detailed yet readable primer. We’d suggest reading our recent series on mains and high voltage safety before cracking open a switch-mode PSU yourself, but even if you’re never going to do it there’s something to be gained from knowing in detail how they work.

We’ve featured [Lindsay]’s work here at Hackaday a few times over the years. Check out his ultrasonic transducer power supply, which might be of use were you were building the ultrasonic soldering iron we featured not long ago, his laser stripping of ribbon cables, and his tale of decapping a USB isolator chip.