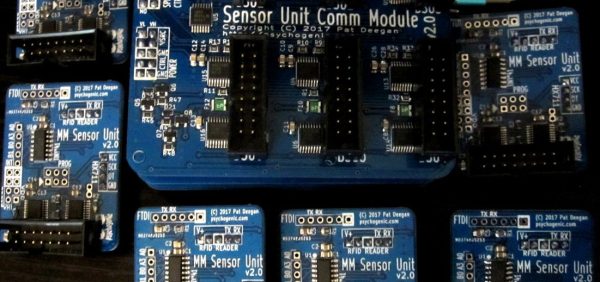

When working on a project that needs to send data from place to place the distances involved often dictate the method of sending. Are the two chunks of the system on one PCB? A “vanilla” communication protocol like i2c or SPI is probably fine unless there are more exotic requirements. Are the two components mechanically separated? Do they move around? Do they need to be far apart? Reconfigurable? A trendy answer might be to add Bluetooth Low Energy or WiFi to everything but that obviously comes with a set of costs and drawbacks. What about just using really long wires? [Pat] needed to connect six boards to a central node over distances of several feet and learned a few tricks in the process.

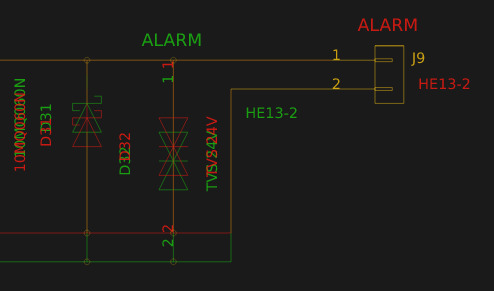

When connecting two nodes together via wires it seems like choosing a protocol and plugging everything in is all that’s required, right? [Pat]’s first set of learnings is about the problems that happen when you try that. It turns out that “long wire” is another way to spell “antenna”, and if you happen to be unlucky enough to catch a passing wave that particular property can fry pins on your micro.

When connecting two nodes together via wires it seems like choosing a protocol and plugging everything in is all that’s required, right? [Pat]’s first set of learnings is about the problems that happen when you try that. It turns out that “long wire” is another way to spell “antenna”, and if you happen to be unlucky enough to catch a passing wave that particular property can fry pins on your micro.

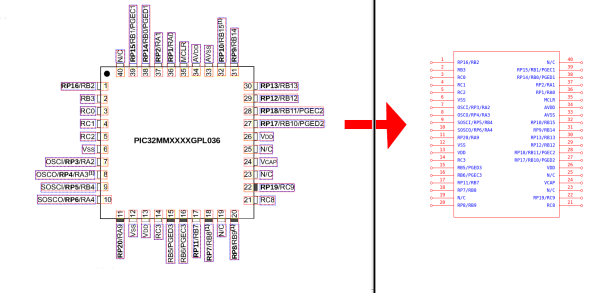

Plus it turns out wires have resistance proportional to their length (who would have though!) so those sharp square clock signals turn into gently rolling hills. Even getting to the point where those rolling hills travel between the two devices requires driving drive the lines harder than the average micro can manage. The solution? A differential pair. Check out the post to learn about one way to do that.

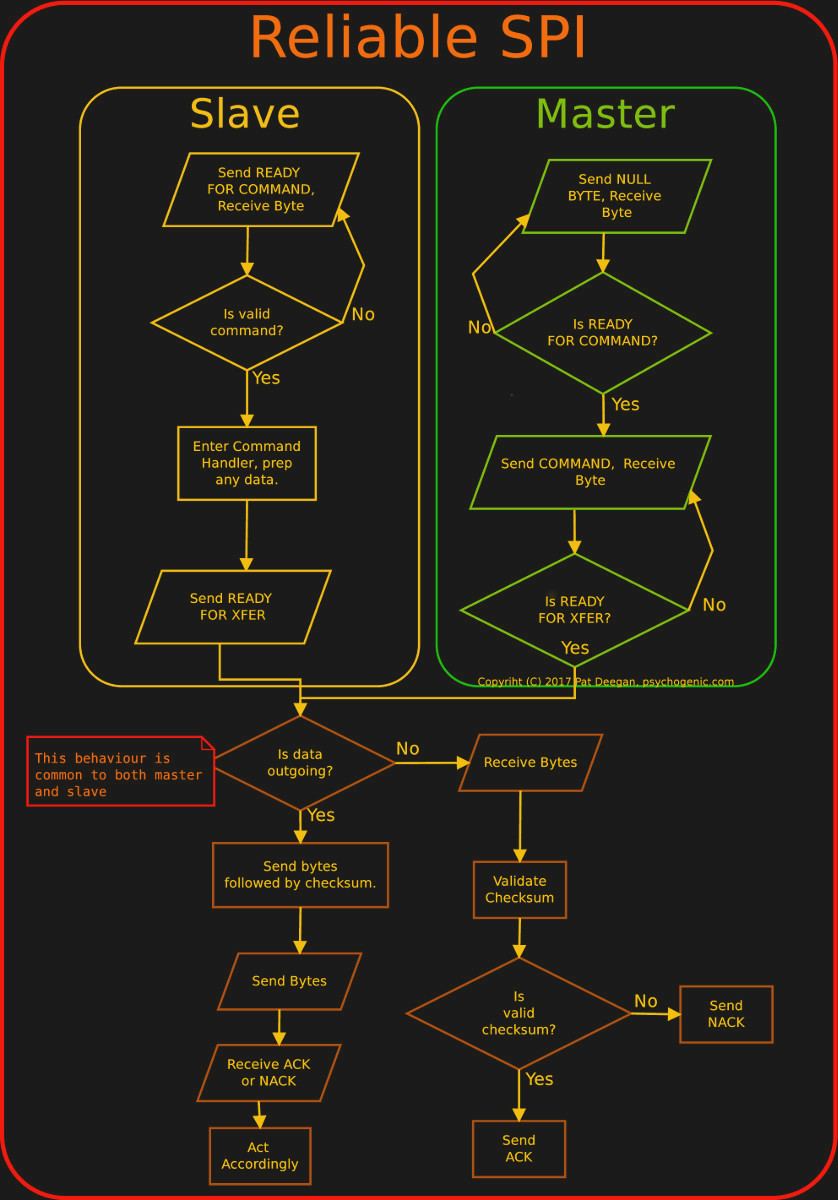

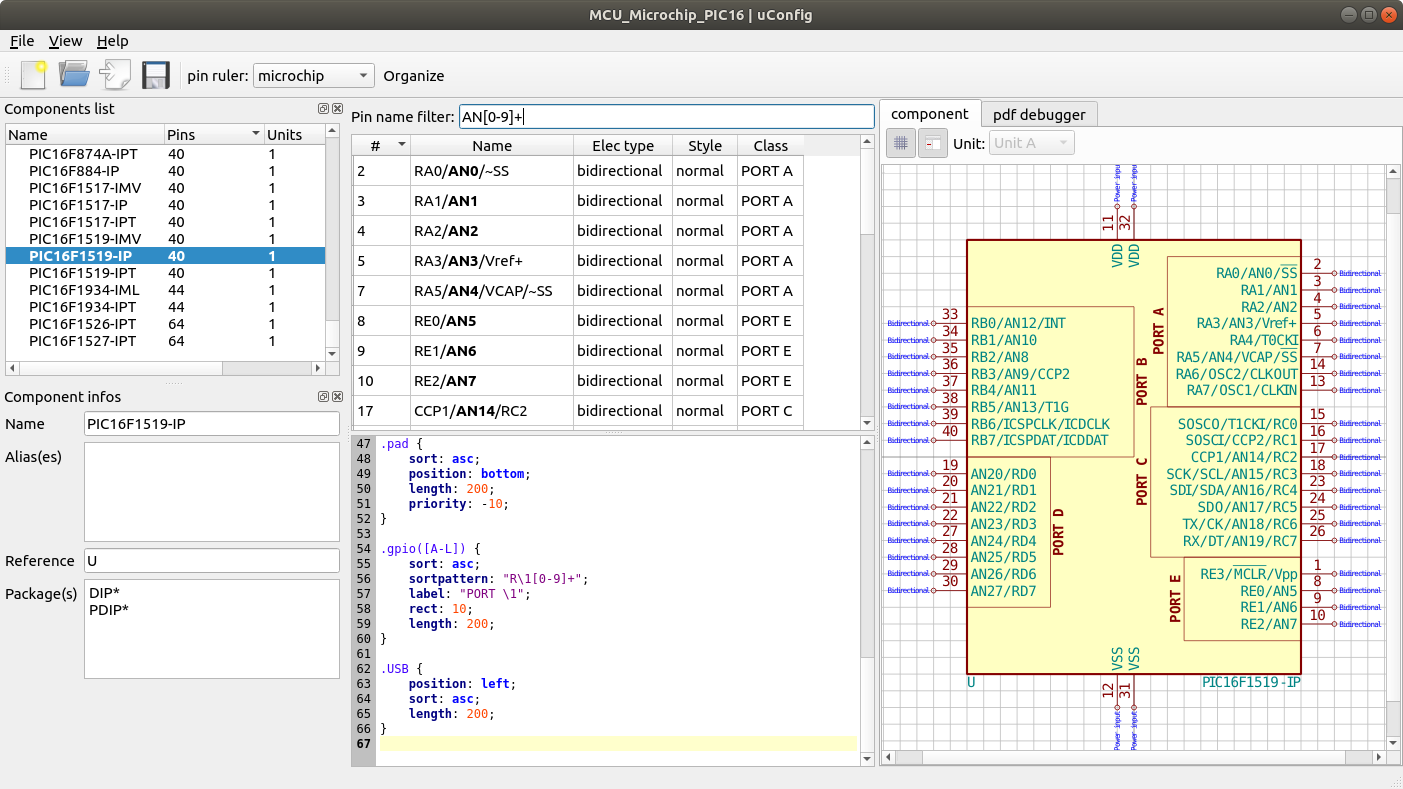

It looks like [Pat] needed to add USB to this witches brew and ended up choosing a pretty strange part from FTDI, the Vinculum II. The VNC2 seemed like a great choice with a rich set of peripherals and two configurable USB Host/Peripheral controllers but it turned out to be a nightmare for development. [Pat]’s writeup of the related troubles is a fun and familiar read. The workaround for an incredible set of undocumented bad behaviors in the SPI peripheral was to add a thick layer of reliability related messaging on top of the physical communication layer. Check out the state machine for a taste, and the original post for a detailed description.

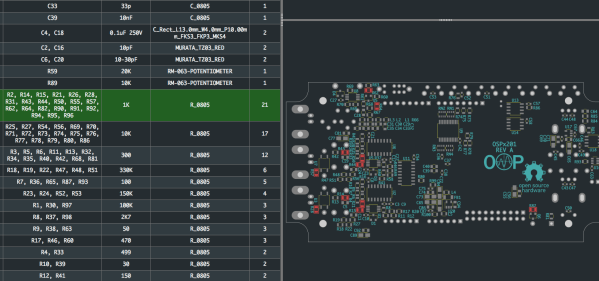

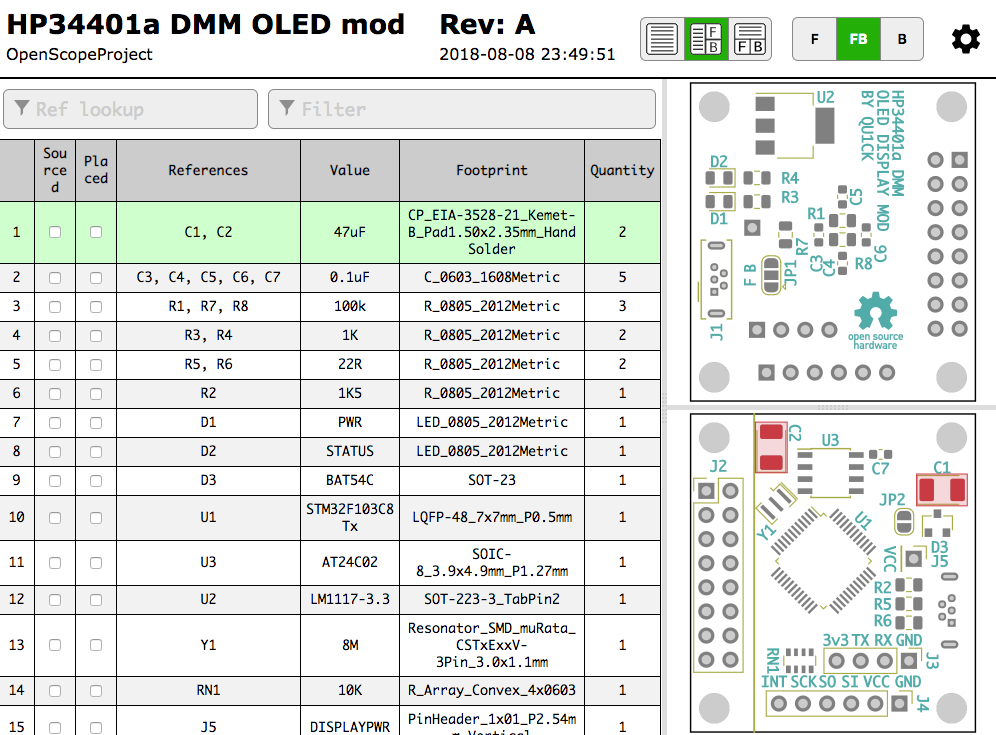

The full MatchSticks creation flow goes like this:

The full MatchSticks creation flow goes like this: