While we don’t often see them in the hobbyist community, 3D printers that can extrude gels and viscous liquids have existed commercially for years, and are increasingly used for biological research. [Ahron Wayne] has recently been working with such a printer as part of a project to develop a printed wound dressing made of honey and blood clotting proteins, but for practice purposes, wanted to find a cheaper and more common material that had similar extrusion properties.

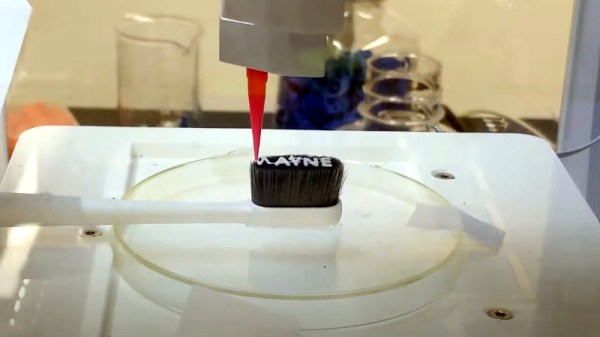

The material he settled on ended up being common toothpaste. In the video below you can see him loading up the cartridge of a CELLINK INKREDIBLE+ bioprinter with the minty goop, which is then extruded through a thin blunt-tip needle by compressed air. After printing out various shapes and words using the material, often times directly onto the bristles of a toothbrush, he’s come up with a list of tips for printing similarly viscous substances.

The material he settled on ended up being common toothpaste. In the video below you can see him loading up the cartridge of a CELLINK INKREDIBLE+ bioprinter with the minty goop, which is then extruded through a thin blunt-tip needle by compressed air. After printing out various shapes and words using the material, often times directly onto the bristles of a toothbrush, he’s come up with a list of tips for printing similarly viscous substances.

First and foremost, go slow. [Ahron] says the material needs a moment to contract after being extruded if it’s going to have any hope of supporting the next layer of the print. Thick layer heights are a necessity, as is avoiding sharp curves in your design. He also notes that overhangs must be avoided, and though it probably goes without saying, clarifies that an object printed from toothpaste will never be able to support anything more than its own weight.

In addition to the handful of legitimate DIY bioprinters that have graced these pages over the years, we’ve seen the occasional chocolate 3D printer that operated on a similar principle to produce bespoke treats, so the lessons learned by [Ahron] aren’t completely lost on the hacker and maker crowd. Who knows? Perhaps you’ll one day find yourself consulting this video when trying to get a modified 3D printer to lay down some soldering paste.

Continue reading “3D Printing Toothpaste In The Name Of Science”