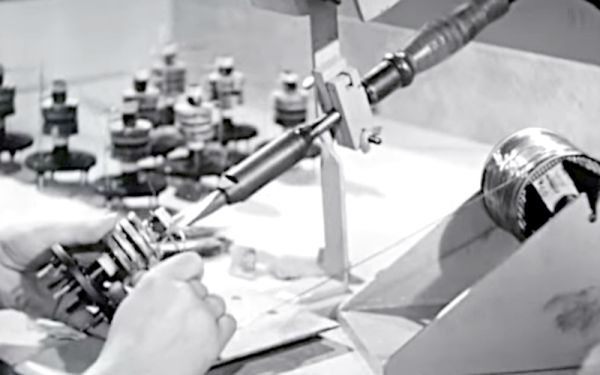

We’ve seen some absolutely gorgeous freeform circuit sculptures. There’s a mystic quality to taking what has normally been hidden away for safety and reliability reasons and putting it on display for everyone to see. Of course, creating these unique circuit sculptures takes considerable time and effort. [Inne] created several silicone soldering jigs to help with these tricky joints.

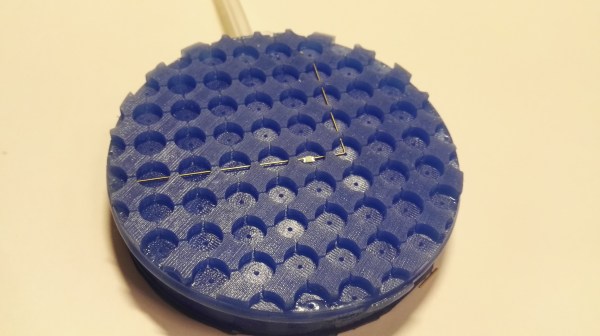

While a vice or helping hands is crucial for many joints, when dealing with tiny SMD components and exacting angles, you need something a little more specialized. Double-sided tape is often recommended, but heat ruins the adhesive and SMD components like to stick to soldering iron tips. Since silicone tends to be heat resistant, it makes a decent material for soldering on. [Inne] uses a city analogy with the cups for soldering called plazas, each with a hole (called a manhole) leading to a foot-switch vacuum pump to keep parts in place. The OpenSCAD code is available on GitHub under a GPLv3 license. It generates a two-part mold that you can cast in A-8/A-15 silicone.

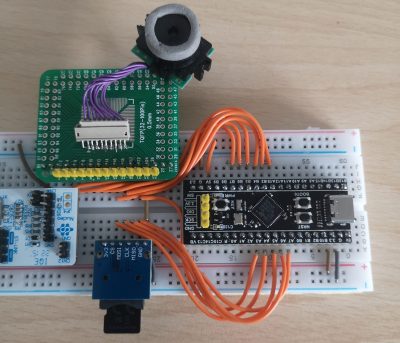

It’s a clever project that makes it far easier to assemble gorgeous circuit sculptures. We love the design and thought that went into it, particularly the naming scheme as we often find appropriately naming variables in OpenSCAD quickly becomes difficult.