We’ve seen plenty of environmental monitoring setups here on Hackaday — wireless sensors dotted around the house, all uploading their temperature and humidity data to a central server hidden away in some closet. The system put together by [Andy] from Workshopshed is much the same, except this time the server has been designed to be as bright and bold as possible.

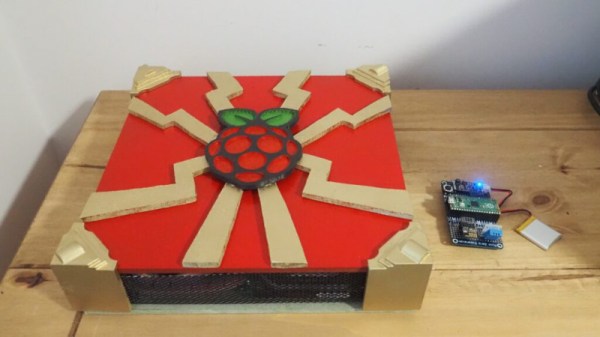

The use of Mosquitto, InfluxDB, Node Red, and Grafana (M.I.N.G) made [Andy] think of Ming the Merciless from Flash Gordon, which in turn inspired the enclosure that holds the Raspberry Pi, hard drive, and power supply. Some 3D printed details help sell the look, and painted metal mesh panels make sure there’s plenty of airflow.

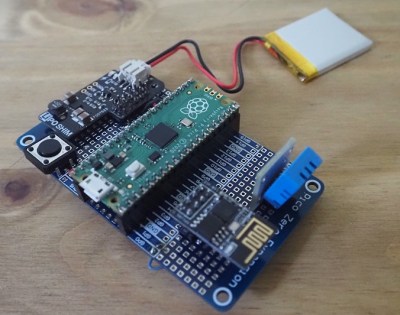

While the server is certainly eye-catching, the sensors themselves are also worth a close look. You might expect the sensors to be based on some member of the ESP family, but in this case, [Andy] has opted to go with the Raspberry Pi Pico. As this project pre-dates the release of the wireless variant of the board, he had to add on an ESP-01 for communications as well as the DTH11 temperature and humidity sensor.

While the server is certainly eye-catching, the sensors themselves are also worth a close look. You might expect the sensors to be based on some member of the ESP family, but in this case, [Andy] has opted to go with the Raspberry Pi Pico. As this project pre-dates the release of the wireless variant of the board, he had to add on an ESP-01 for communications as well as the DTH11 temperature and humidity sensor.

For power each sensor includes a 1200 mAh pouch cell and a Pimoroni LiPo SHIM, though he does note working with the Pico’s energy saving modes posed something of a challenge. A perfboard holds all the components together, and the whole thing fits into an understated 3D printed enclosure.

Should you go the ESP8266/ESP32 route for your wireless sensors, we’ve seen some pretty tidy packages that are worth checking out. Or if you’d rather use something off-the-shelf, we’re big fans of the custom firmware developed for Xiaomi Bluetooth thermometers.

Continue reading “A Merciless Environmental Monitoring System”