Clear acrylic panels have long been a mainstay of 3D printer enclosure designs, but they can also add significant cost in terms of money, shipping, weight, and hassle. An alternative material worth looking at is corrugated plastic (also known by its trade name coroplast) which is cheap, light, an excellent insulator, and easy to work with. Many enclosure designs can be refitted to use it instead of acrylic, so let’s take a closer look at what it has to offer.

What’s Wrong With Acrylic?

It’s not just the purchase price that makes acrylic a spendy option. Acrylic is fairly heavy, and shipping pieces the size of enclosure panels can be expensive. Also, cutting acrylic without special tools can be a challenge because it cracks easily if mishandled. Acrylic cuts beautifully in a laser cutter, but most laser cutters accessible to a hobbyist are not big enough to make enclosure-sized panels. If you are stuck with needing to cut acrylic by hand, here are some tips on how to get by with the tools you have.

It is best to source acrylic from a local shop that can also cut it to size with the right tools for a reasonable price, but it is still far from being a cheap material. There’s another option: corrugated plastic has quite a few properties that make it worth considering, especially for a hobbyist.

Continue reading “3D Printering: Corrugated Plastic For Cheaper & Easier Enclosures”

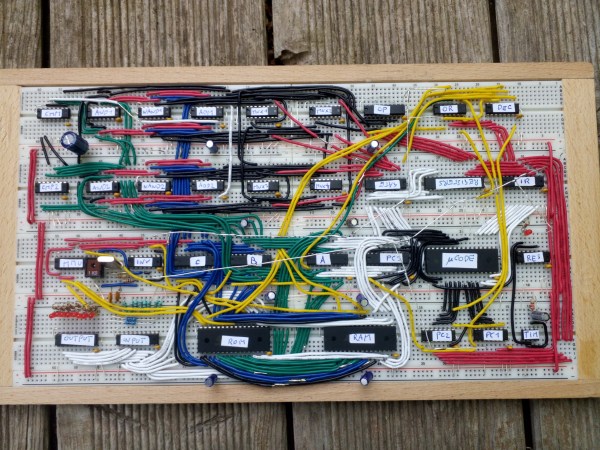

The total circuit is incredibly compact for a complete CPU, using just 33 chips. This includes 64 KB of flash to store programs as well as a 555 timer to generate a clock signal. I/Os are limited to simple eight-bit input and output buses, but a sixteen-bit address bus gives it plenty of space to add ROM, RAM or fancier interfaces.

The total circuit is incredibly compact for a complete CPU, using just 33 chips. This includes 64 KB of flash to store programs as well as a 555 timer to generate a clock signal. I/Os are limited to simple eight-bit input and output buses, but a sixteen-bit address bus gives it plenty of space to add ROM, RAM or fancier interfaces.