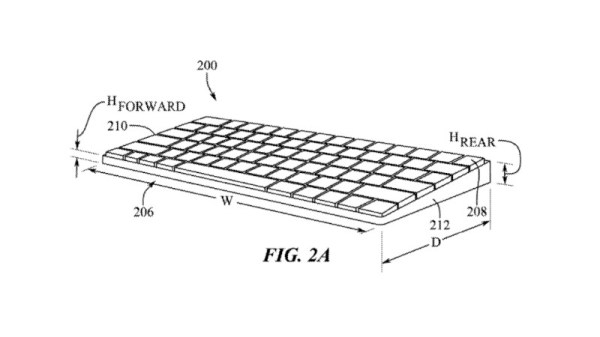

In our recent piece marking the 10th anniversary of the Raspberry Pi, we praised their all-in-one Raspberry Pi 400 computer for having so far succeeded in attracting no competing products. It seems that assessment might be premature, because it emerges that Apple have filed a patent application for “A computer in an input device” that looks very much like the Pi 400. In fact we’d go further than that, it looks very much like any of a number of classic home computers from back in the day, to the extent that we’re left wondering what exactly Apple think is novel enough to patent.

Reading the patent it appears to be a transparent catch-all for all-in-one computers, with the possible exception of “A singular input/output port“, meaning that the only port on the device would be a single USB-C port that could take power, communicate with peripherals, and drive the display. Either way, this seems an extremely weak claim of novelty, if only because we think that a few of the more recent Android phones with keyboards might constitute prior art.

We’re sure that Apple’s lawyers will have their arguments at the ready, but we can’t help wondering whether they’ve fallen for the old joke about Apple fanboys claiming the company invented something when in fact they’ve finally adopted it years after the competition.

Thinking back to the glory days of 8-bit computers for a moment, we’re curious which was the first to sport a form factor little larger than its keyboard. Apple’s own Apple ][ wouldn’t count because the bulk of the machine is behind the keyboard, but for example machines such as Commodore’s VIC-20 or Sinclair’s ZX Spectrum could be said to be all-in-one keyboard computers. Can anyone provide an all-in-one model that predates those two?

You can read our Raspberry Pi 400 review if the all-in-one interests you.

Via Extreme Tech.