Engineering is all about making a design that conforms to a set of requirements. Usually those are boring things like cost, power consumption, volume, mass or compatibility with existing systems. But sometimes, you have to design something with restrictions you might have never considered. [Devon Bray] was tasked with designing a system that could dispense single drops of water, while making absolutely no noise. [Devon]’s blog describes in detail the process of making The Silent Dripper, which was needed for an art installation called The Tender Interval by [Sara Dittrich].

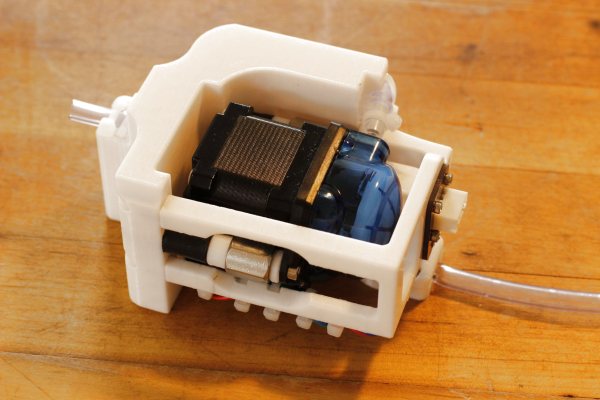

The design process started with picking a proper pump. Centrifugal pumps can be very quiet due to their smooth, continuous motion, but are not suitable for moving small quantities of liquid. Peristaltic pumps on the other hand can generate single drops of liquid very accurately, but their gripping-and-squeezing motion creates far more sound. [Devon] still went for the latter type, and eventually discovered that filling up the pumping mechanism with lithium grease made it quiet enough for his purpose.

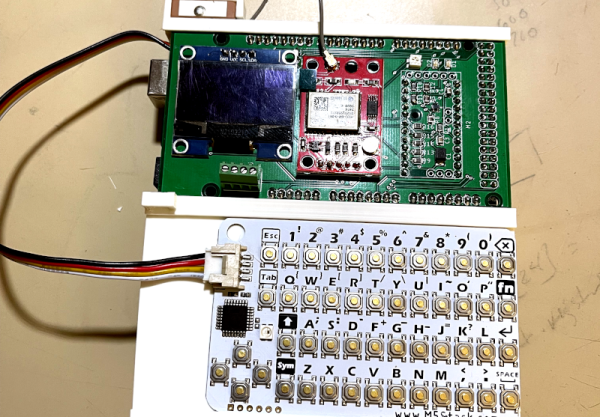

The pump was then mounted on a 3D-printed bracket that also contained the water feeding tube and electrical connections to the outside world. The tubing was fastened with zip ties to stop it from moving when the pump was running, and the pump itself was isolated from the bracket with rubber dampening mounts.

Another trick to silence the pump was the motor driver circuit: standard PWM drivers often cause audible whine from the motor coils because of their abrupt switching, so [Devon] went for a Trinamic SilentStepStick that regulates the current much more smoothly. The end result is a water dripper that makes less noise than a piece of tissue paper being crumpled, as you can observe in the video (embedded below) which also demonstrates the complete art installation.

We really like the mechanical design of the Dripper; as far as we’re concerned it would merit a spot in a gallery on its own. It would not be the first water dripping art project either; we’ve already seen a sculpture that apparently suspends droplets in mid-air. Continue reading “The Silent Dripper Dispenses Water Without Making Any Sound” →