Weaving is one of the oldest crafts in the world, and was also among the first to be automated: the Industrial Revolution was in large part driven by developments in loom technology. [Roger de Meester] decided to recreate that part of the industry’s history, in a way, by building his own desktop-sized, fully automatic loom. After a long career in the textiles industry he’s quite the expert when it comes to weaving, and as you’ll see he’s also an expert machine builder.

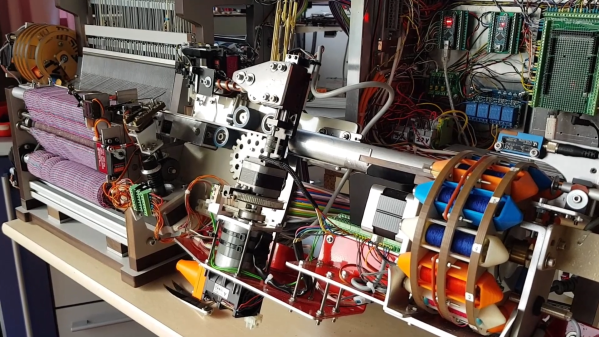

[Roger]’s loom is of a specific type called a dobby loom, which means that the vertical threads (the warp) can be moved up and down in various ways to create different patterns in the fabric. The horizontal wires (the weft) are created by a shuttle moving left and right, carrying a bobbin that unspools as it travels. A comb-shaped plate (the reed) then fixes the fresh weft in its place. [Roger]’s videos (embedded below) clearly show this mechanism in action, as well as the loom’s overall design.

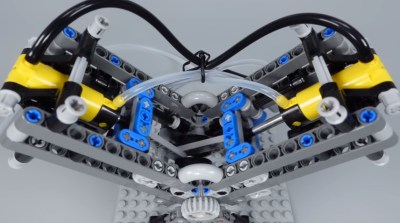

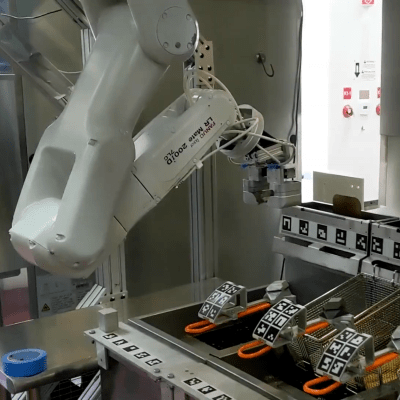

The 3D printed shuttle is moved back and forth through the warp by a belt-driven system that grabs the magnetic end of the shuttle. Revolving storage drums on either side of the machine enable the use of different thread colors for each shuttle run. Shuttles are exchanged by a robotic arm that picks them up and places them onto the track; there’s a clamp that grabs the end of the thread as the shuttle starts its run, and a wire cutter to detach it when the shuttle is up for replacement.

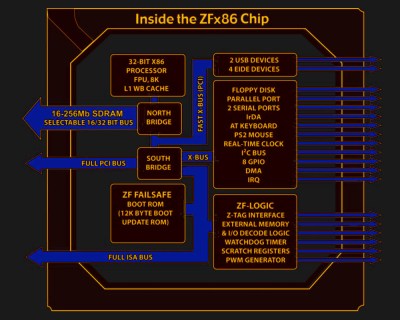

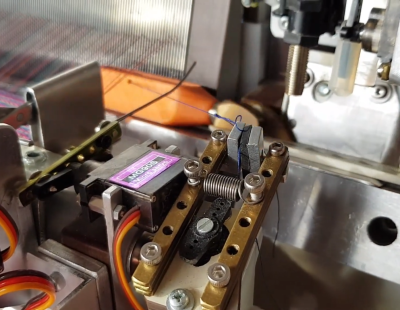

This intricate mechanical dance is controlled by a set of Arduino Megas and Nanos. They drive all the servos, DC motors, and steppers while reading out an array of sensors and switches. The system can even detect several faults: the weft is checked for proper tension after each cycle, shuttles with empty bobbins are automatically discarded, while a laser keeps an eye on the warp to ensure none of the threads have snapped.

The entire machine is of [Roger]’s own design; apart from 3D-printed and CNC-machined parts, he also re-used components from various pieces of discarded machinery. His ultimate purpose is to use this machine to make specialized fabrics for medical or industrial use: for example, it can use conductive threads to make fabrics with built-in sensors.

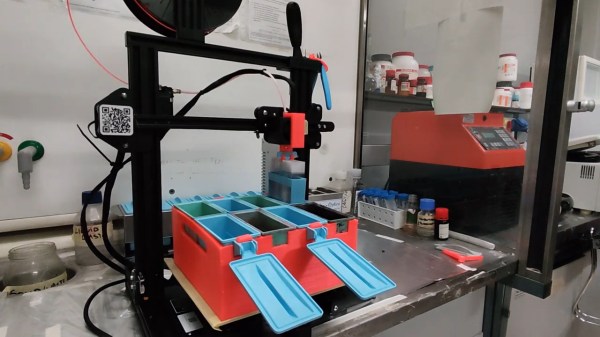

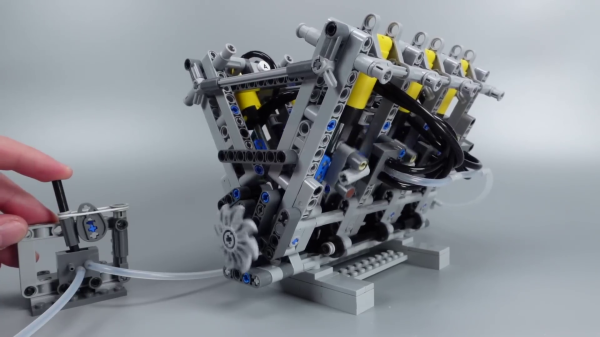

Although this isn’t the first DIY automatic loom we’ve featured, it’s definitely the most advanced. Previous examples, like this 3D-printed miniature version or this neat computer-controlled one can’t really compare to [Roger]’s 26 cm reed width and wide customizability. If you prefer to keep things a bit simpler, you can also use a 3D-printer to directly print certain fabrics.

Continue reading “Desktop-Sized Fully Automatic Loom Is An Electromechanical Marvel”