By taking advantage of persistence in human vision, we can use modest bits of hardware to create an illusion of a far larger display. We’ve featured many POV projects here, but they are almost always an exploration in two dimensions. [Jamal-Ra-Davis] extends that into the third dimension with his Volumetric POV Display.

Having already built a 6x6x6 LED cube, [Jamal] wanted to make it bigger, but was not a fan of the amount of work it would take to grow the size of a three-dimensional array. To sidestep the exponential increase in effort required, he switched to using persistence of vision by spinning the light source and thereby multiplying its effect.

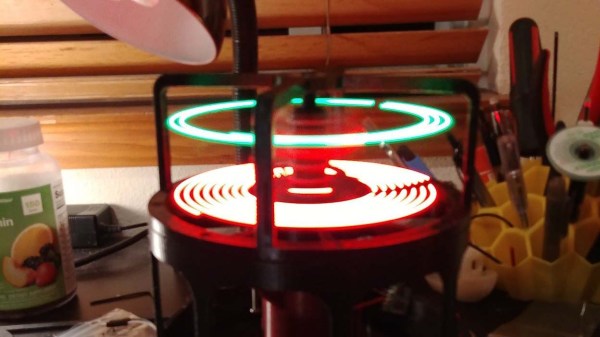

The current version has six arms stacked vertically, each of which presents eight individually addressable APA102 LEDs. When spinning, those 48 LEDs create a 3D display with an effective resolution of 60x8x6.

We saw an earlier iteration of this project a little over a year ago at Bay Area Maker Faire 2018. (A demo video from that evening can be found below.) It was set aside for a while but has now returned to active development as an entry to Hackaday Prize 2019. [Jamal-Ra-Davis] would like to evolve his prototype into something that can be sold as a kit, and all information has been made public so others can build upon this work.

We’ve seen two-dimensional spinning POV LED display in a toy top, and we’ve also seen some POV projects taking steps into the third dimension. We like where this trend is going.

Continue reading “A Multi-Layered Spin On Persistence Of Vision”