Now that 3D printers have more or less hit the mass market, hackers need a new “elite” tool to spend their time designing and fiddling with. Judging by the last couple of years, it looks like laser cutters will be taking over as the hacker tool du jour; as we’re starting to see more and more custom builds and modifications of entry-level commercial models. Usually these are limited to relatively small and low powered diode lasers, but as the following project shows, that’s not always the case.

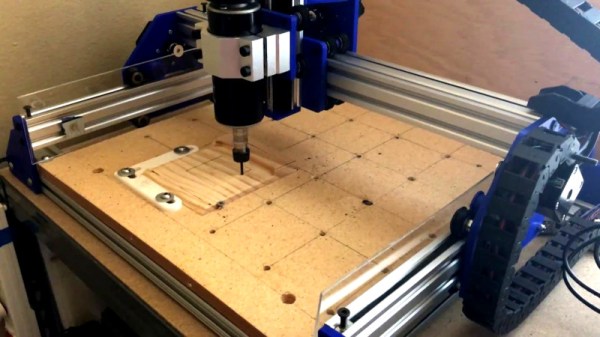

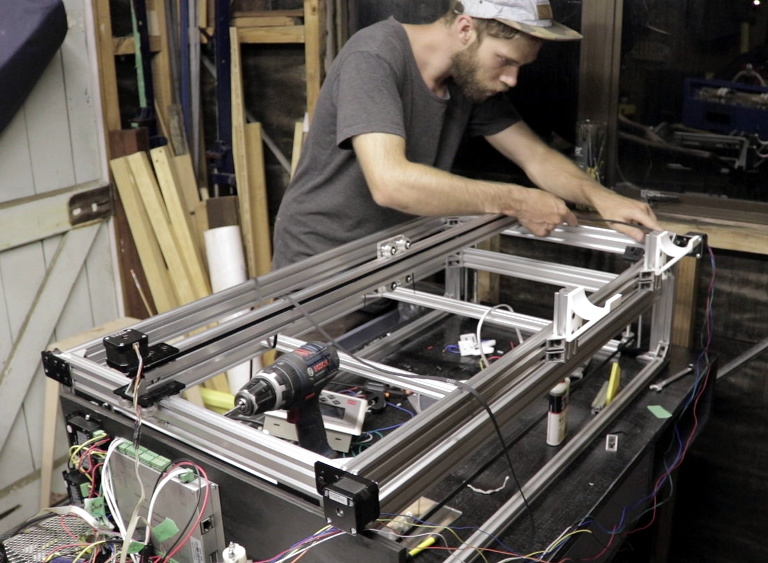

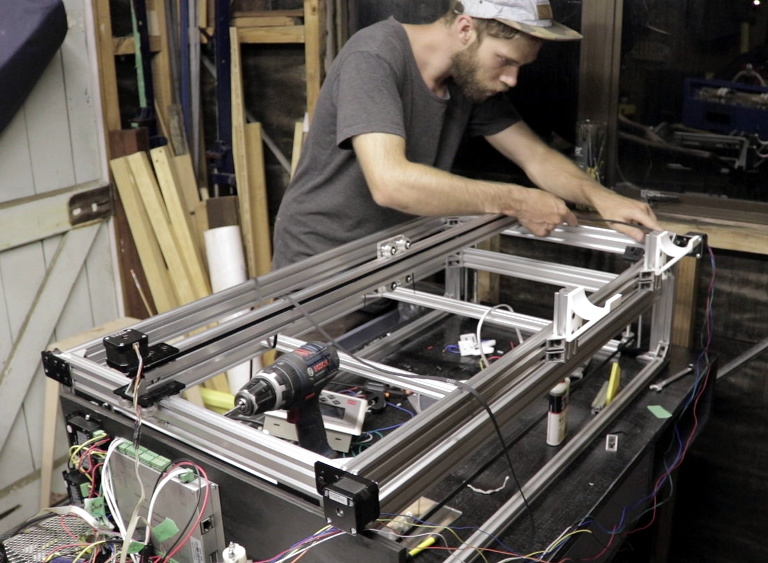

This large format laser cutter designed and built by [Rob Chesney] is meticulously detailed on his blog, as well as in the in the video after the break. It’s made up of aluminium profile and a splattering of ABS 3D printed parts, and lives in an acrylic enclosure that’s uniquely isolated from the laser’s internal gantry. All told it cost about $2,000 USD to build, but considering the volume and features of this cutter that’s still a very fair price.

This large format laser cutter designed and built by [Rob Chesney] is meticulously detailed on his blog, as well as in the in the video after the break. It’s made up of aluminium profile and a splattering of ABS 3D printed parts, and lives in an acrylic enclosure that’s uniquely isolated from the laser’s internal gantry. All told it cost about $2,000 USD to build, but considering the volume and features of this cutter that’s still a very fair price.

[Rob] carefully planned every aspect of this build, modeling the entire machine in CAD before actually purchasing any hardware. Interestingly enough his primary design constraint was the door to his shed: he wanted to build the largest possible laser cutter that could still be carried through it. That led to the final machine’s long and relatively shallow final dimensions. The design was also guided by a desire to minimize material waste, so when possible parts were designed to maximize how many could be cut from a one meter length of aluminum extrusion.

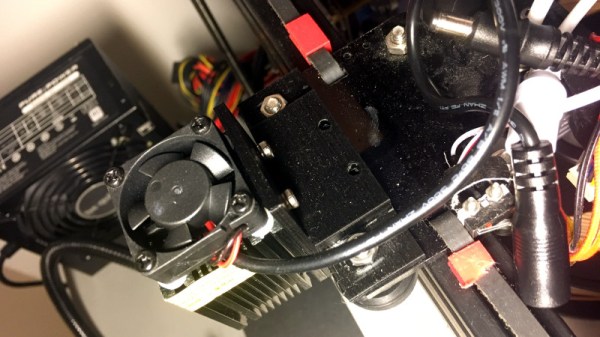

The laser features a movable Z axis that’s similar in design to what you might see in a Prusa-style 3D printer, with each corner of the gantry getting an 8 mm lead screw and smooth rod which are used in conjunction to lift and guide. All of the lead screws are connected to each other via pulleys and standard GT2 belt, but as of this version, [Rob] notes the Z axis must be manually operated. In the future he’ll be able to add in a stepper motor and automate it easily, but it wasn’t critical to get the machine running.

He used 3D printed parts for objects which had a relatively complex geometry, such as the laser tube holders and Z axis components, but more simplistic brackets were made out of cut acrylic. In some components, [Rob] used welding cement to bond two pieces of acrylic and thereby double the thickness. Large acrylic panels were also used for the laser’s outer enclosure, which was intentionally designed as a separate entity from the laser itself. He reasoned that this would make assembly easier and faster, as the enclosure would not have to be held to the same dimensional tolerances as it would have been if it was integrated into the machine.

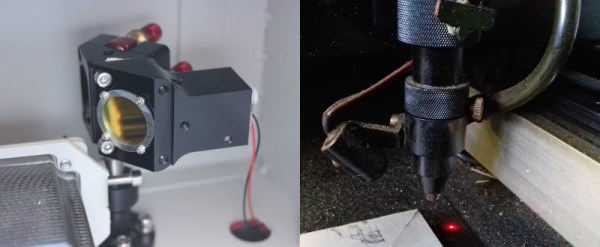

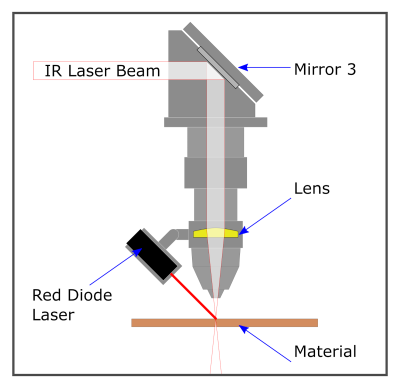

[Rob] gives plenty of detail about all the finer points of water cooling, laser control electronics, aligning the mirrors, and really anything else you could possibly want to know about building your own serious laser cutter. If you’ve been considering building your own laser and have anything you’re curious or unsure about, there’s a good chance he addresses it in this build.

Short of having the fantastically good luck to find a laser cutter in the trash that you can refurbish, building your own machine may still be the best upgrade path if you outgrow your eBay K40.

Continue reading “Scratch-Building A Supersized Laser Cutter” →