Turn the clock back six decades or so and imagine you’re in the nascent computer business. You know your product has immense value, but only to a limited customer base with the means to afford such devices and the ability to understand them and put them to use. You know that the market will eventually saturate unless you can create a self-sustaining computer culture. But how does one accomplish such a thing in 1961?

Enter the Minivac 601. The brainchild of no less a computer luminary than Claude Shannon, the father of information theory, the Minivac 601 was ostensibly a toy in the vein of the “100-in-1” electronics kits that would appear later. It used electromechanical circuits to teach basic logic, and now [Mike Gardi] has created a replica of the original Minivac 601.

Both the original and the replica use relays as logic switches, which can be wired in various configurations through jumpers. [Mike]’s version is as faithful to the original as possible with modern parts, and gets an extra authenticity boost through the use of 3D-printed panels and a laser-cut wood frame to recreate the look of the original. Sadly, the unique motorized rotary switch, used for both input and output on the original, has yet to be fully implemented on the replica. But everything else is spot on, and the vintage look is great. Extra points to [Mike] for laboriously recreating the original programming terminals with solder lugs and brass eyelets.

We love seeing this retro replica, and appreciate the chance to reflect on the genius of its inventor. Our profile of Claude Shannon is a great place to start learning about his other contributions to computer science. We’ve also got a deeper dive into information theory for the curious.

Thanks to [Granz] for the tip.

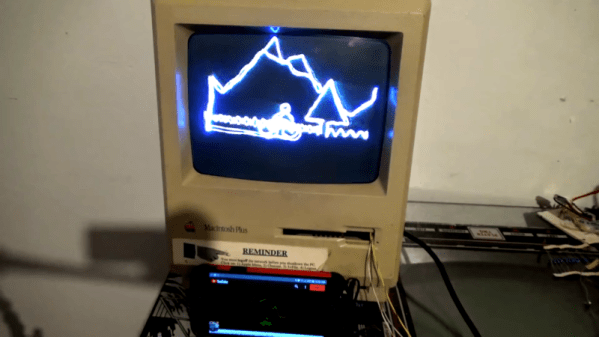

The hack starts with the opening of a Macintosh, which naturally requires a long screwdriver with the right tip. Setting the stage for things to come, this is achieved by soldering together a couple of existing tools to get the reach he needs. [Jason] then proceeds to install a brightness control for the main electron gun, as well as deflection drivers and a spot killing circuit. Everything is done with the intention of the hack being reversible, as [Jason] didn’t wish to sacrifice a good Macintosh Plus just for the sake of having some fun.

The hack starts with the opening of a Macintosh, which naturally requires a long screwdriver with the right tip. Setting the stage for things to come, this is achieved by soldering together a couple of existing tools to get the reach he needs. [Jason] then proceeds to install a brightness control for the main electron gun, as well as deflection drivers and a spot killing circuit. Everything is done with the intention of the hack being reversible, as [Jason] didn’t wish to sacrifice a good Macintosh Plus just for the sake of having some fun.