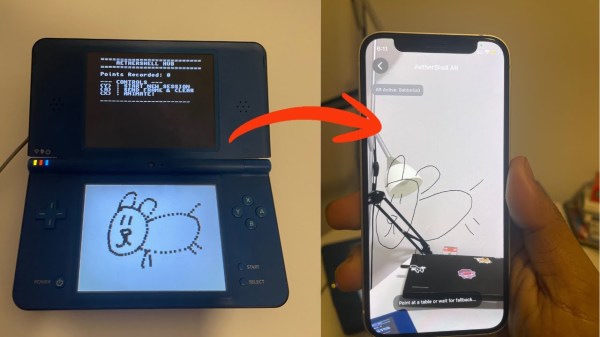

Although there are a few hobbies that have low-cost entry points, amateur astronomy is not generally among them. A tabletop Dobsonian might cost a few hundred dollars, and that is just the entry point for an ever-increasing set of telescopes, mounts, trackers, lasers, and other pieces of equipment that it’s possible to build or buy. [Thomas] is deep into astronomy now, has a high-quality, remotely controllable telescope, and wanted to make it more accessible to his friends and others, so he built a system that lets the telescope stream on Twitch and lets his Twitch viewers control what it’s looking at.

The project began with overcoming the $4000 telescope’s practical limitations, most notably an annoyingly short Wi-Fi range and closed software. [Thomas] built a wireless bridge with a Raspberry Pi to extend connectivity, and then built a headless streaming system using OBS Studio inside a Proxmox container. This was a major hurdle as OBS doesn’t have particularly good support for headless operation.