We know what you’re thinking: with so many wireless modules available for just pennies, trying to create a physical data link using ultrasonic transducers like [Damian Bonicatto] did for a short-range, low-bitrate remote monitoring setup seems like a waste of time. And granted, there are a ton of simple RF protocols you can just throw at a job like this. Something like this could be done and dusted for a couple of bucks, right?

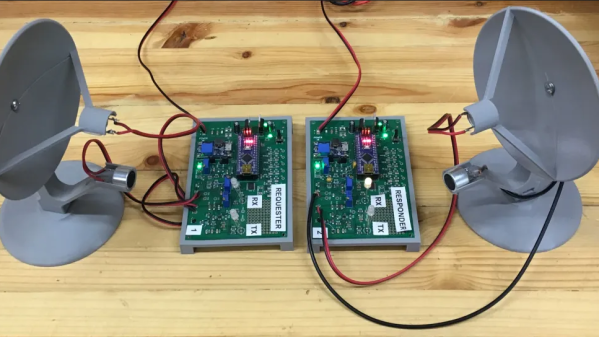

Luckily, [Damian] wanted something a little different for his wireless link to a small off-grid solar array, which is why he started playing with ultrasound in an SDR framework. The design for his “Software-Defined Ultrasonics” system, detailed in Part 1, has a pair of links, each with two ultrasonic transducers, one for receiving and one for transmitting. Both connect to audio amplifiers with bandpass filters; the received signal is digitized by the ADC built into an Arduino Nano, while the transmitted signal is converted to analog by an outboard DAC.

The transducers are affixed to 3D printed parabolic reflectors, which are aimed at each other over a path length of about 150′ (46 m). Part 2 of the series details the firmware needed to make all this work. A lot of the firmware design is dictated by the constraints introduced by using Arduinos and the 40-kHz ultrasonic carrier, meaning that the link can only do about 250 baud. That may sound slow, but it’s more than enough for [Damian]’s application.

Perhaps most importantly, this is one of those times where going slower helps you to go faster; pretty much everything about the firmware on this system applies to SDRs, so if you can grok one, the other should be a breeze. But if you still need a little help minding your Is and Qs, check out [Jenny]’s SDR primer.