The International Space Station is one of our leading frontiers of science and engineering, but it’s easy to forget that an exotic orbiting laboratory has basic needs shared with every terrestrial workplace. This includes humble office equipment like a printer. (The ink-on-paper kind.) And if you thought your office IT is slow to update their list of approved equipment, consider the standard issue NASA space printer draws from a stock of modified Epson Stylus 800s first flown on a space shuttle almost twenty years ago. HP signed on to provide a replacement, partnering with Simplexity who outlined their work as a case study upgrading HP’s OfficeJet 5740 design into the HP Envy ISS.

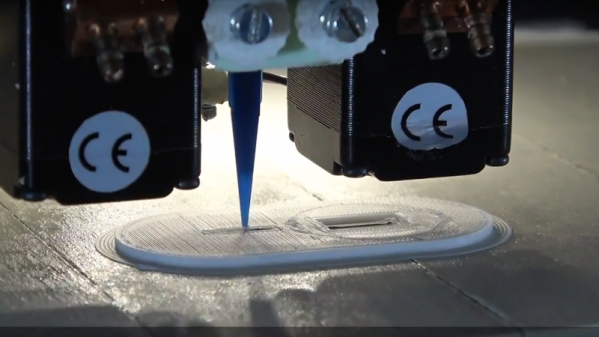

Simplexity provided more engineering detail than HP’s less technical page. Core parts of inkjet printing are already well suited for space and required no modification. Their low power consumption is valued when all power comes from solar panels, and ink flow is already controlled via methods independent of gravity. Most of the engineering work focused on paper handling in zero gravity, similar to the work necessary for its Epson predecessor. To verify gravity-independent operation on earth, Simplexity started by mounting their test units upside-down and worked their way up to testing in the cabin of an aircraft in free fall.

CollectSpace has a writeup with details outside Simplexity’s scope, covering why ISS needs a printer plus additional modifications made in the interest of crew safety. Standard injection-molded plastic parts were remade with an even more fire-resistant formulation of plastic. The fax/scanner portion of the device was removed due to concerns around its glass bed. Absorbent mats were attached inside the printer to catch any stray ink droplets.

NASA commissioned a production run for 50 printers, the first of which was delivered by SpaceX last week on board their CRS-14 mission. When it wears out, a future resupply mission will deliver its replacement drawn from this stock of space printers. Maybe a new inkjet printer isn’t as exciting as 3D printing in space or exploring space debris cleanup, but it’s still a part of keeping our orbital laboratory running.

NASA commissioned a production run for 50 printers, the first of which was delivered by SpaceX last week on board their CRS-14 mission. When it wears out, a future resupply mission will deliver its replacement drawn from this stock of space printers. Maybe a new inkjet printer isn’t as exciting as 3D printing in space or exploring space debris cleanup, but it’s still a part of keeping our orbital laboratory running.

[via Engadget]